Masterpiece Story: The Climax by Aubrey Beardsley

Aubrey Beardsley’s legacy endures, etched into the contours of the Art Nouveau movement. His distinctive style, marked by grotesque imagery and...

Lisa Scalone 27 October 2024

Gustav Klimt, born in Austria in 1862, is one of the most valued artists in the history of art. But, what is Klimt famous for? Why exactly do we value his work? And what role did he play in modern art and culture?

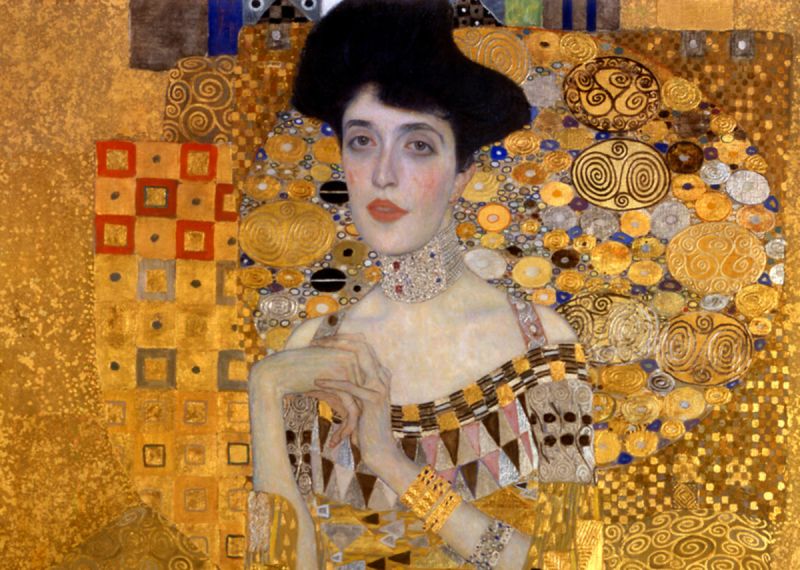

In 2006, Ronald Lauder, the collector of Austrian Expressionist art and co-founder of the New York Expressionist museum, Neue Galerie, spent an extraordinary $135 million on a single painting: Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, a Viennese socialite and patroness of the arts. For a short while, this work became the most expensive painting in the world.

Gustav Klimt’s works might be exclusive, but they’ve also come to adorn cheap tats—mugs, key rings, tea towels—you can almost find anything with Klimt printed on it. There’s definitely a certain quality in his work that attracts not just art cognoscenti, but a much wider public, regardless of their familiarity with the artist’s work or reputation. Everybody seems to want a piece of Klimt.

Alfred Weidinger, Klimt expert and the vice-director of the Belvedere Museum in Vienna, which holds the biggest collection of Klimt, found the artist’s appeal to be truly universal. In 2009, as he was travelling around Africa, he met a woman in the rural south of Ethiopia, wearing a T-shirt of Klimt’s The Kiss.

She explained that an Italian photographer who had visited her village earlier offered her to choose from three T-shirts as a thank-you gift. Despite knowing nothing about the artist, she chose the Klimt because of the gold in the image.

So the metallic look and decorative effect of Klimt’s work attracts people, Weidinger concluded.

Son of a goldsmith, Klimt understood the material better than every other of his contemporaries. Later, as a poor student at the School of Applied Art in Vienna, he took inspiration from the dazzle of Byzantine Art. His early works often emulated the effects and colors of precious metals and stones. And as soon as monetary concerns were out of the way, he started using actual gold.

The decorative and luminous effects of the paintings might make any gaudy item look expensive. But the value of the masters’ work lies beyond the opulence of gems and gold. Klimt was one of the fathers of Viennese Modern art, who broke away from the artistic past.

What do we mean by artistic past? It’s kind of a philosophical question. Conservative art academies posited that the purpose of art was to recreate the three-dimensional reality with a two-dimensional surface of a canvas, just the way we see it in real life. This tradition could be traced to the use of perspective since the 14th century, during the Italian Renaissance. Artists at that time maintained that the frame of a painting should function more or less like a window to perceive the reality external to us.

However, Klimt refused to copy what was in front of him. He instead turned to scientists, biologists, and psychologists of his time. Their findings on evolution and the inner workings of the human mind influenced Klimt’s art as much as they did for Vienna as a city between 1890 and 1918.

Klimt realized the traditional way of perceiving reality was insufficient to express the breakthroughs beyond our visible world. So he started breaking the rules of perspective, blocking his canvases with patterns, shapes, and symbols. That way, Klimt became a forerunner of Austrian Modernism.

Early 20th-century Vienna was the center of European culture and science. Unlike New York, London, or Paris, where professionals of one field form communities among their own, Viennese artists, writers, scientists, and physicians mixed and mingled. Gymnasiums and universities were epicenters for sharing the latest scientific achievements, and the conversations went way beyond those institution walls. Socialite Berta Zuckerkandl and her husband, Emil Zuckerkandl, both people of science, often held parties, meetings, and lectures that Klimt used to frequent.

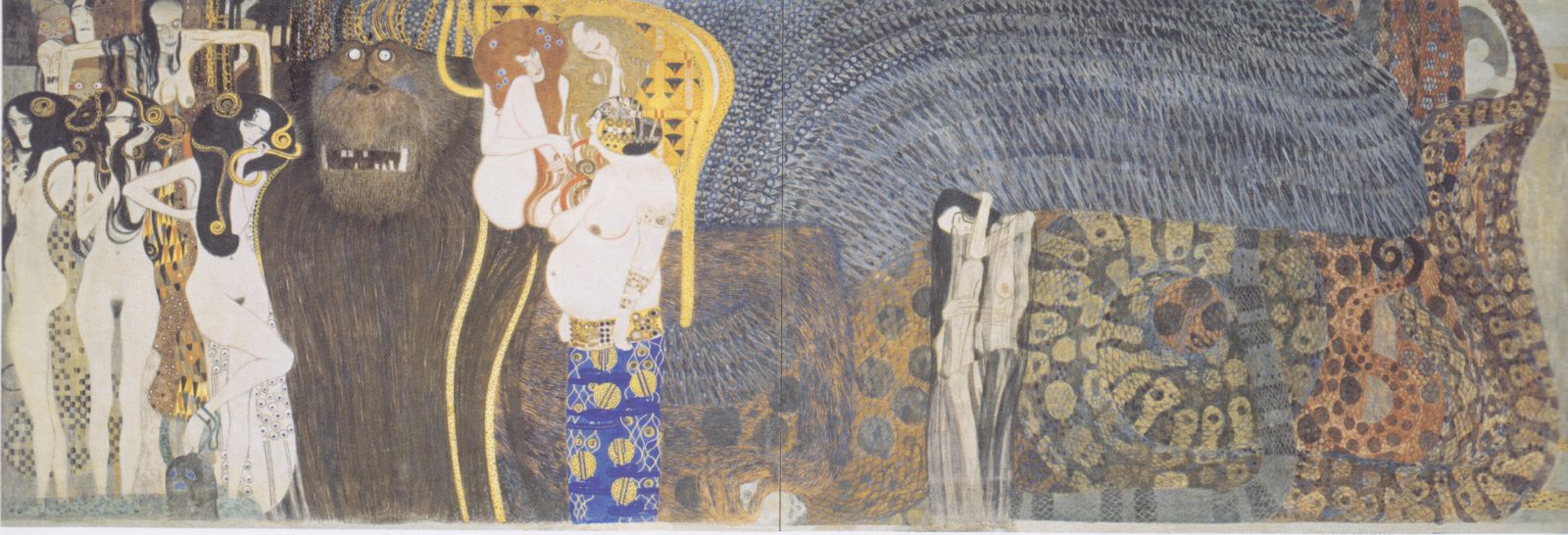

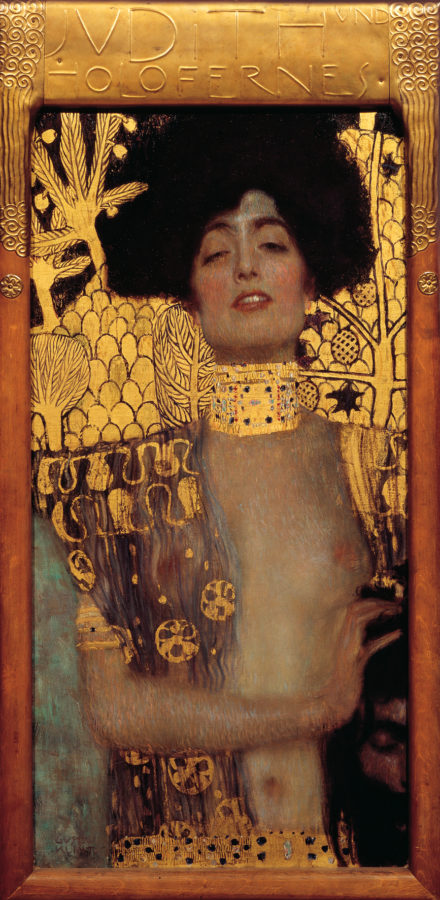

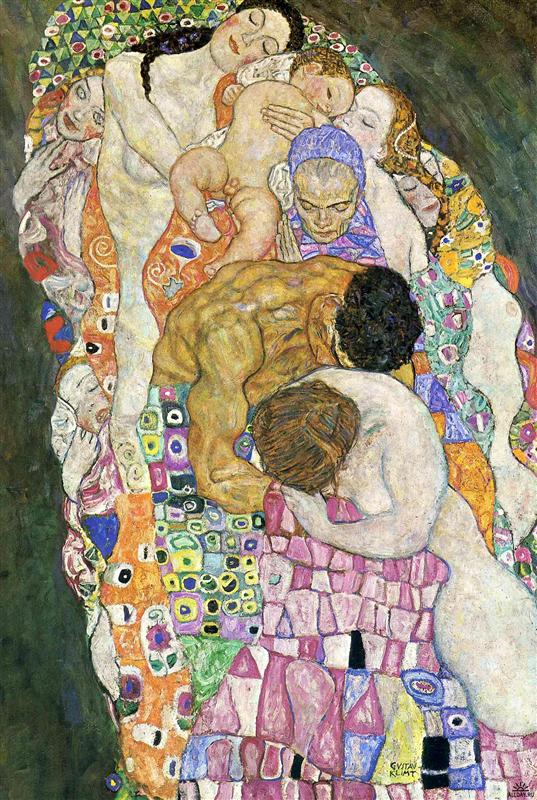

Klimt read Darwin and followed developments in the field of biology and embryology. He was fascinated by how a single cell—such as a human egg, is fertilized and develops into a fetus and then, through various stages, into an infant. That’s why he often “adorned” his paintings with biological symbols, which added an esoteric layer of meaning to his work. The sensual and beatific women on his canvases weren’t just entertaining male erotic fantasies; they also embodied one of the greatest mysteries of all times—the creation of life.

In his Hope I, a naked woman stands in front of us in her final stage of pregnancy. Art historian Emily Braun noticed that the dark-blue, primitive, sea-creature-like form winding behind the woman’s swollen belly echoes a prevailing view at that time, namely, that the development of a human embryo follows the same path as human evolution. This view was suggested by the German biologist Ernst Haeckel, who believed that human embryos possess gills and tails reminiscent of their primitive, fishlike ancestors but lose those features as they develop.

Back to the famous Portrait of Adele, the shapes and patterns on Adele’s dress are not just decorative. Instead, they symbolize male and female cells: rectangular sperm and ovoid eggs. As art historian Emily Braun puts it:

These biologically inspired fertility symbols are designed to match the sitter’s seductive face to her full-blown reproductive capabilities.

Emily Braun in: Eric Kandel, The Age of Insight, Random House, New York, 2012.

Finally, one of his most famous works, Danaë, is also a full-blown celebration of female fertility and conception. Klimt incorporated the same biological symbols. Here, on the left side of the canvas, the artist translates Zeus coming to Danaethe as a shower of golden raindrops into black rectangles, symbolizing Zeus’s masculinity. He also included early embryonic forms, symbolizing conception, on the right side.

Through observing his friend, anatomist Emil Zuckerkandl, dissecting bodies at the University of Vienna, Gustav Klimt gained a profound understanding of human anatomy. As Eric Kandel wrote about the artist’s work:

…nude bodies [in Klimt’s works] stand just for itself, as a biological species subject to the same procreative laws as every other organism.

Eric Kandel, The Age of Insight, Random House, New York, 2012.

Even after scrutinizing Gustav Klimt’s work from a sterile biological point of view, we cannot escape the striking sensual aura his canvases create. Beneath all the intellectual reasoning, all of us are ruled by a sexual urge that most of us oppress but so few of us can tame.

This is the domain of another Viennese giant: Sigmund Freud. The father of modern psychoanalysis and Klimt’s contemporary, Freud opened the door of the unconscious mind to modern science. Through his scrupulous study of dreams and the psychological conditions of his patients, he discovered that the unconscious mind is mostly ruled by our need for procreation (and the rest by our compulsion for aggressiveness).

Many artists studied the female body, but Klimt’s nudes were too realistic, intimate, provocative, and outrageous for his time. What’s remarkable about Klimt, is that, like Freud, he created a visual dialogue with his sitter in an attempt to understand female sexuality. Unlike Freud, the notorious womanizer he was, his studies of the subject didn’t just end with a drawing session.

Through his work, Klimt sees the process of human reproduction and development in a naturalistic, evolutionary light. That makes him not just a painter or a decorator but also an innovative thinker of the past century.

Stephanie Hegarty, Gustav Klimt: What’s the secret to his mass appeal?, BBC, 2012. Accessed: Jan. 31, 2025.

Eric Kandel, The Age of Insight, Random House, New York, 2012.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!