Apollo and Daphne in 5 Artworks

From Ancient Rome to the Renaissance and Rococo, the timeless appeal of the Apollo and Daphne myth spans centuries of artistic expression. The myth...

Anna Ingram 30 January 2025

During the middle of the 18th century, landscape gardening became valued higher than a work of art in England. Landscape gardener William Chambers was employed by the Princess of Wales for her Gardens at Kew in London from 1757 to 1762. As an established architect and designer, he was famous for the two Chinese buildings he designed. Here are the surviving watercolors and pictures of the Royal Gardens at Kew from the 18th century.

Historically in the 18th century Great Britain, men were favored as the innovators of landscape garden designs and interiors. William Kent and William Chambers are credited today for developing the popular English landscape garden designs (also known as the “picturesque” garden). A blossoming interest in chinoiserie interiors and garden buildings was happening simultaneously in Europe due to trade markets with China. Chambers’ designs for the Royal Gardens at Kew are the best example of the 18th-century landscape garden trend.

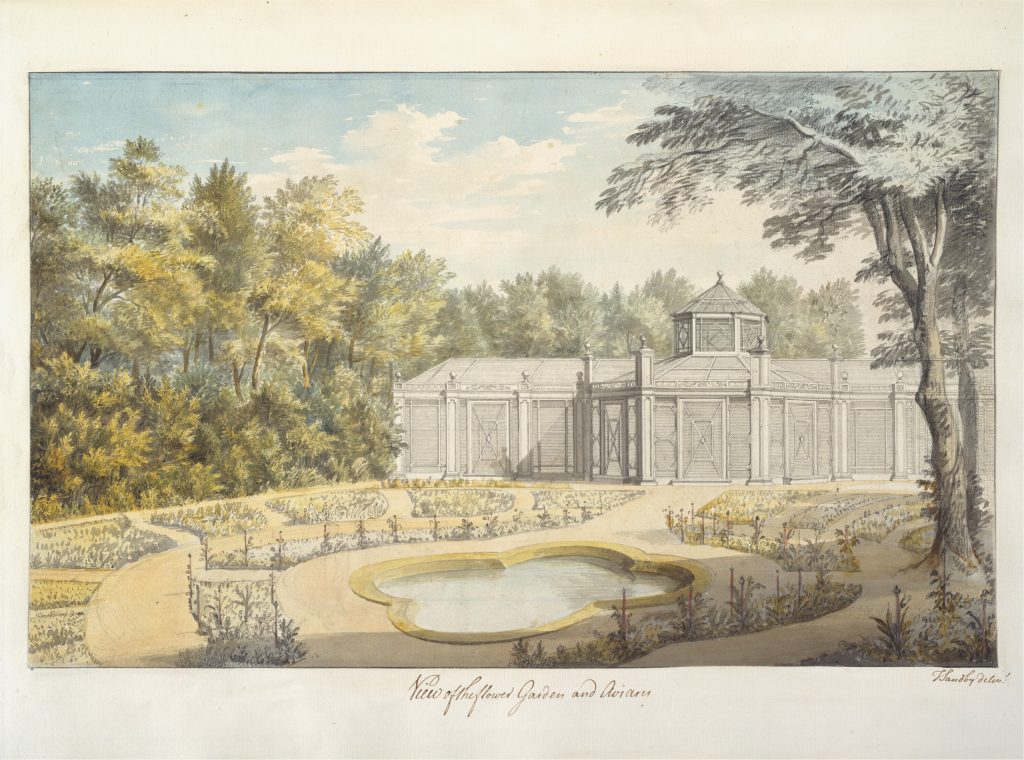

Thomas Sandby, View of the Flower Garden and Aviary at Kew, watercolor, 1763, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

Interestingly, at 16 Chambers sailed with the Swedish East India Company to the Far East on a trade expedition. Then at the age of 20, he studied architecture in Italy and France. Eventually, he moved to the trade city of Canton, China, where he saw Chinese imports pass through to Great Britain. He collected countless sketches of Chinese architecture through his fascination with the surrounding buildings and designs.

When Chambers returned to London his reputation attracted the Earl of Bute. Luckily, the nobleman introduced Chambers to the Dowager Princess of Wales, who hired him to design her Gardens at Kew from 1757 to 1762. For the rest of his life, Chambers was fortunate enough to have royal favor.

By 1750, wealthy noblemen and women possessed some Chinese porcelain, Chinese silks, or wallpaper. Although lacquerware had been familiar for a long time in England, what began to appear was furniture with Chinese designs and Chinese pavilions in English landscape gardens.

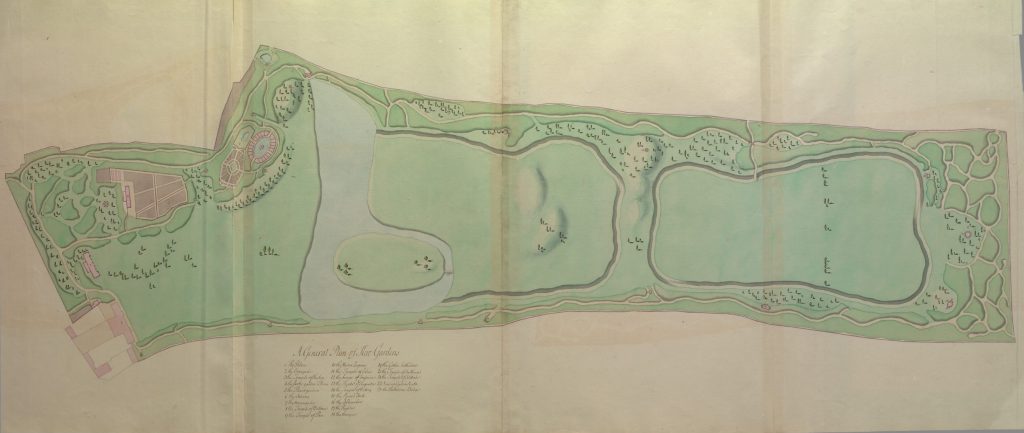

William Chambers, General Plan for the Gardens at Kew, 1763, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

Since so many properties included chinoiserie garden buildings, they became the primary signifier of China in British landscape gardens. Chinoiserie garden structures played a similar role to what chinoiserie did inside the house: it signified commerce, cosmopolitanism, and novelty for the patron. Rather than the previous geometrical European garden, Chinese garden elements incorporated a more established presence of commodity within the British landscape.

Because many Londoners had not traveled to China before, William Chambers transported visitors through his garden designs in the Garden of Kew. The watercolor by Thomas Sandby, View of the Menagerie at Kew, clearly shows the influence of Chinese building designs. However, there is more to this garden design than just the chinoiserie building…

Thomas Sandby, View of the Menagerie at Kew, watercolor, 1763, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

Assuming that China must be accessed by water, garden designers placed the Chinese buildings in English gardens near water. This idea created an interactive experience where the visitor would be able to conceptualize a journey across the sea by crossing a bridge. This is best expressed through William Chambers’ Chinese pavilion in the center of a lake near the menagerie at the Garden of Kew. Here, the Chinese pavilion sits in the middle of a lake and one can only access it by bridge.

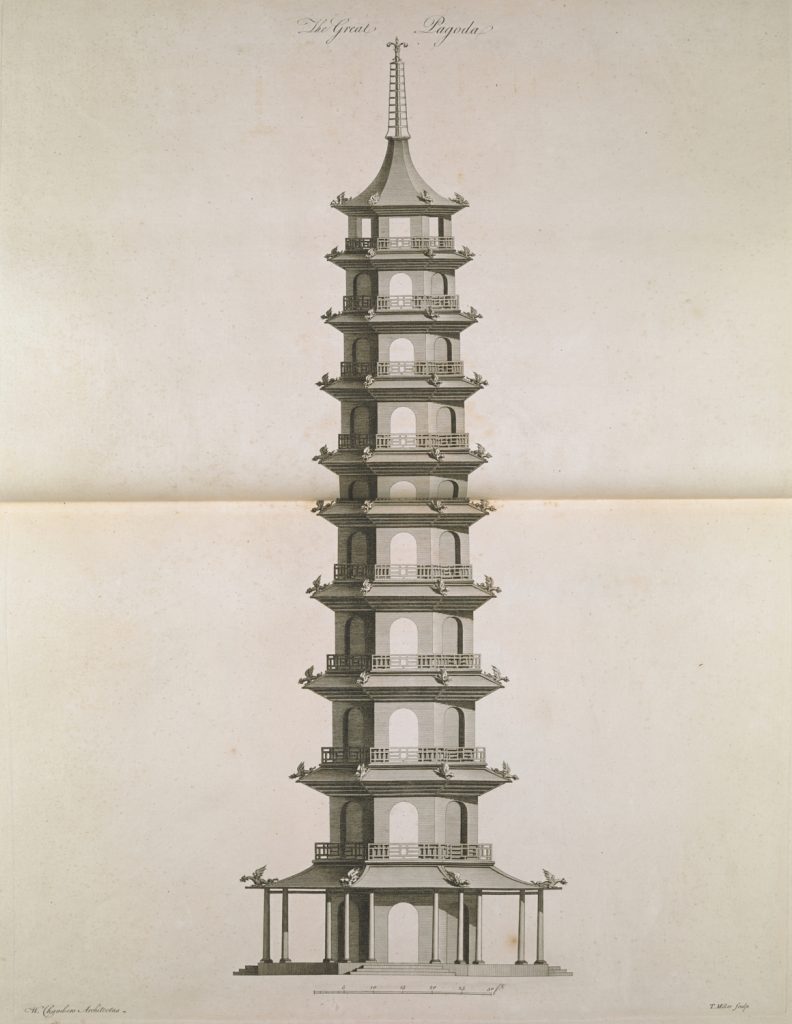

William Chambers, The Great Pagoda, etching, engraving, 1765, The British Library, London, UK.

The second Chinese building William Chambers designed in the Garden of Kew was the Great Pagoda. “Constructed in 1761-62, the Great Pagoda is one of the most recognizable chinoiserie buildings in Europe” states Lee Prosser, curator of historic buildings at the Historic Royal Palaces. Historic Royal Palaces is an independent charity that takes care of five British Palaces, including Kew Palace. The pagoda standing there today is not the original though. It was altered during the late 19th century to mimic its predecessor.

Although the influence of China is fascinating, chinoiserie buildings were not the only eclectic features included in gardens during the 18th century.

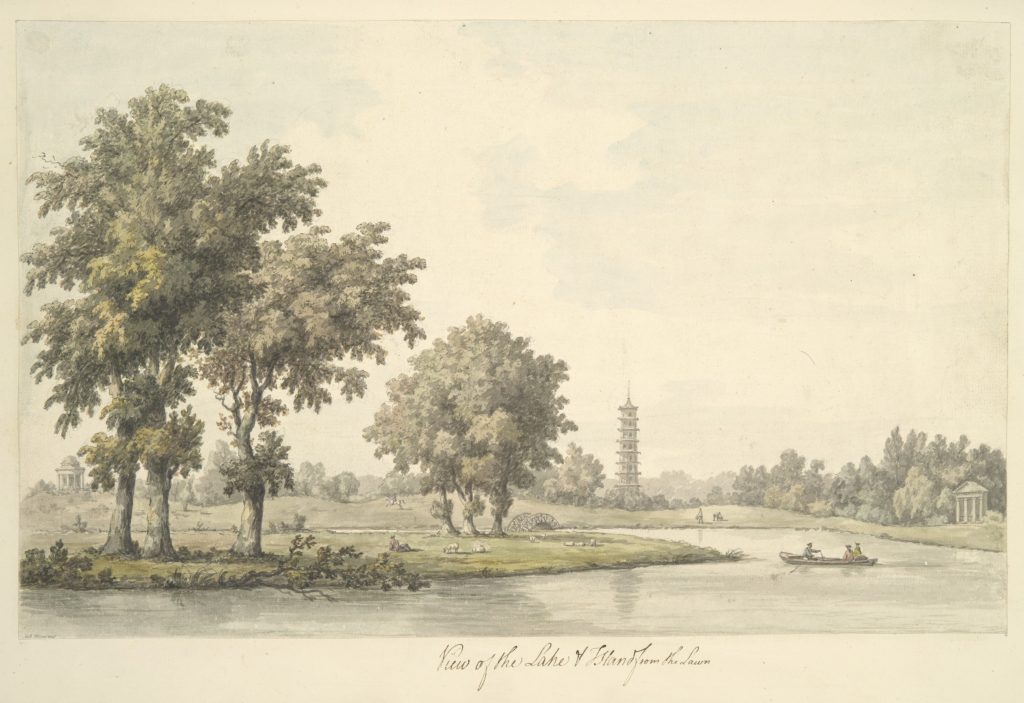

William Marlow, View of the Lake and the Island from the Lawn at Kew, watercolor, 1763, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

For example, the “picturesque” elements of the gardens at Kew are better seen through a painting by William Marlow. In this painting, Marlow provides a glimpse at Chambers’ garden design and architectural structures. If you look closely you can see the inclusion of a mosque, a classical rotunda, and a Chinese pagoda. This watercolor from 1763 perfectly encompasses the fascination with diverse styles in 18th-century British landscape gardens.

However, Chambers’ imitations at Kew, such as the pagoda seen in the distance of this image, were praised for their authenticity.

The Great Pagoda as restored in its modern landscape setting, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, London, UK. Cambridge University Press.

Upon the garden’s completion in 1763, Chambers published a text explaining his work at Kew, called Plans, Elevations, Sections, Perspective Views of the Gardens and Buildings at Kew. It is important to note that Chambers was the first trained architect to publish architectural drawings of Chinese buildings.

One scholar notes that before the end of the 18th century, garden pagodas were seen in Holland, France, and Germany while Chinese pavilions existed in Spain and Sweden. Thus it seems William Chambers’ influence on Chinese-style buildings and designs reached further and lasted longer than it did in England.

Robert C. Bald, “Sir William Chambers and the Chinese Garden.” Journal of the History of Ideas 11, no. 3 (1950): 287-320.

Stacey Sloboda, “Commerce in the garden: nature, art, and authority.” In Chinoiserie: Commerce and Critical Ornament in Eighteenth-Century Britain, Manchester University Press, 2014.

John Dixon Hunt and Peter Willis, eds. The Genius of the Place: The English Landscape Garden, 1620–1820. London: Elek, 1975.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!