Apollo and Daphne in 5 Artworks

From Ancient Rome to the Renaissance and Rococo, the timeless appeal of the Apollo and Daphne myth spans centuries of artistic expression. The myth...

Anna Ingram 30 January 2025

11 November 2021 min Read

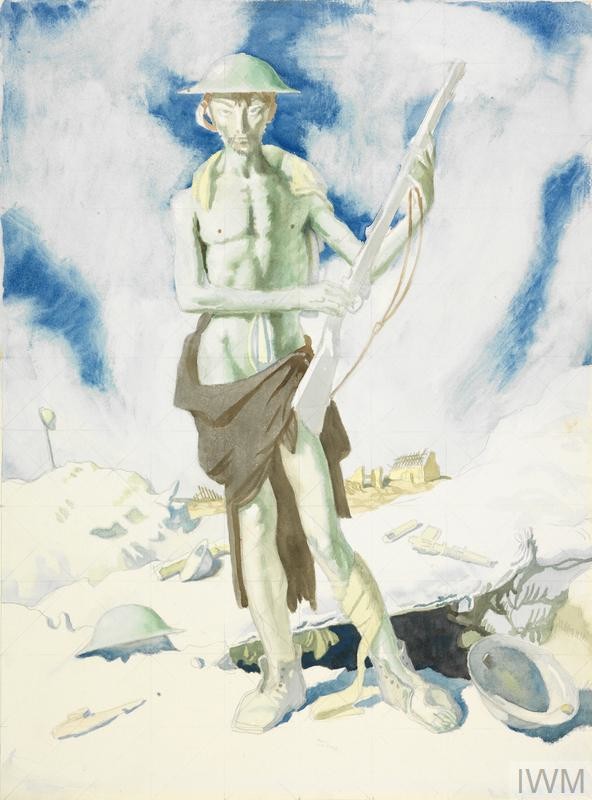

Initially known for society portraits, Sir William Orpen (the knighthood came after the end of the war) became an official artist of the First World War. He produced works of such stunning yet horrific reality, that they still have the power to shock today.

Three paintings in particular draw us to the the differences that this war brought to our understanding of how it should be portrayed. In the past, artists were expected to produce scenes showing the glory of war, patriotism and heroism in equal measure. In the preface of his memoir, ‘An Onlooker in France 1917-1919’, Orpen said:

The only thought I wish to convey is my sincere thanks for the wonderful opportunity that was given to me to look on and see the fighting man, and to learn to revere and worship him.

Regardless of whether he was looking at the British or German sides of the conflict, Orpen revered the human sacrifice with a steely determination to ‘tell it like it is’.

This painting was reluctantly passed by the official censor after Orpen used his connection to the Director of Military Intelligence to ask him to intervene in the censor’s decision to ban this painting. Understandably, the censor would not have been happy with Orpen’s decision to show a sympathetic response to the German dead. However this scene of quiet decay after the war machine has moved on, cannot fail to evoke sympathy. The lighting of this scene is incredibly stark, creating a calcified effect. Orpen uses no half-tones, a blue-green depicts the decay of the two men left behind. The bright light does not allow us to push them into the shadows. This was the reality and this is how Orpen wished us to see the consequences of what was taking place.

In his memoir, Orpen wrote:

I remember an officer saying to me, Paint the Somme? I could do it from memory – just a flat horizon line and mudholes and water, and the stumps of a few battered trees.’ but one could not paint the smell.”

In Zonnebeke, Orpen records the battleground where the Fifth Battle of Ypres had taken place; and if ever a painting might affect all of the senses, it is this one. Orpen spoke of the scenes he had witnessed and brought to life on this canvas:

“A hand lying on the duckboards, a Bosche and a Highlander locked in a deadly embrace at the edge of Highwood; the ‘Cough-Drop’ with the stench coming from its watery bottom; the shell-holes with the shapes of bodies faintly showing through the putrid water – all these things made one think terribly of what human beings had been through.”

Commissioned after the war by the Imperial War Museum to create a work that celebrated the peace process, Orpen found himself increasingly disillusioned. Having been asked to paint individual portraits of all the political leaders attending the Peace Conference, Orpen was growing increasingly disillusioned with what he described at the ‘frock coats’ taking all the glory while the ones who died and who suffered to bring about the peace, were being forgotten.

In this his third canvas on the subject, Orpen began another panorama of those who had taken part in the Peace Conference, but then painted everyone out. He replaced them with the coffin of the unknown soldier, covered with a Union Jack, flanked by two semi-naked guards and cherubs floating above in the Hall of Peace at the Palace of Versailles.

The guards were based on Orpen’s earlier work, Blown Up. Clearly Orpen was keeping to the idea of “looking on and see the fighting man” and thereby honoring him in this way.

The Imperial War Museum, however, was not impressed and they rejected the painting saying “It did not show what we wished shown,” and they withheld the final payment due to the artist.

In 1928, in tribute to General Haig, Orpen painted out the figures, leaving the memorial to the war dead in solitary position, thereby changing the work from a condemnation of the reality of war, to a homage to the soldier-hero.

Orpen did not shirk from what he felt was his responsibility to the fallen and the wounded and his work is testament to that belief.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!