5 Things You Need to Know About Cupid

Cupid is the ancient Roman god of love and the counterpart to the Greek god Eros. It’s him who inspires us to fall in love, write love songs...

Valeria Kumekina 14 June 2024

Art mirrors society, so this tour of witchcraft in Western art will tell us a lot about our past. We will look at representations of witches from old hags to beautiful seducers and end with the modern witch. Hold on to your broomstick as we fly through time to check out delicious and diabolical sorceresses.

Say the word “witchcraft” and what comes to mind? It probably depends on your cultural and religious background. If you are under 18 it probably means Harry Potter! But for most people the word conjures haggard old women, broomsticks, and bad behavior. For some it might mean nothing more than saucy Halloween costumes. Meanwhile, for others it is a dark and painful part of our social history, in which tens of thousands of women (and some men) were bullied, tortured, and murdered.

Witches in art: Albrecht Dürer, Witch Riding on a Goat, circa 1500, British Museum, London, UK.

The Hebrew Scriptures address witchcraft and the central text of Rabbinic Judaism, the Talmud, also describes punishments for witchcraft. In Homer’s Odyssey from 800 BCE, Circe (shown below) is described as a witch – she turned men into animals. Witchcraft and the supernatural was perfectly normal for the Greeks. It could be beneficial as well as deadly, and was a part of everyday life.

Witches in art: John Waterhouse, Circe Offering the Cup to Odysseus, 1884, Oldham Gallery, Oldham, UK.

The first known witch trials took place in France in 1428. Pope Innocent III published Summis desiderantes affectibus in 1484, speaking of witchcraft as form of Satanism. Meanwhile Heinrich Kramer, a German Catholic clergyman and cruel misogynist, wrote Malleus Maleficarum, a handbook for witch hunters in 1486. He described women as malicious, feeble minded, greedy, and jealous – easy prey for the devil. Their greatest sin, apparently, was their insatiable carnal lust. The very first example of a witch in Western art is shown below.

Witches in art: Martin Le France, Illumination depicting two witches on a broomstick and a stick in Ladies’ Champion, 1451. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

The rise of the printing press allowed panic and religious fervor to spread like wildfire. Malleus Meleficarum was second only to the Bible in terms of sales and circulation. Church politics, family feuds, and hysteria whipped people into a frenzy across Europe and America. Witches were believed to have made a pact with the devil in exchange for powers. From the 15th to the 17th centuries, witchcraft was illegal. Imprisonment, the pillory, or execution by hanging or burning loomed for those accused.

Witches in art: The Discovery of Witches, 1647, British Library, London, UK.

From our earliest ancestors, we have needed a place to put our fears and worries. We want explanations for natural disasters, illness, and suffering. At this point in history, the Plague was a recurring disaster, a “Little Ice Age” had spread across Europe, harvests failed and people starved. For a period in human history, from around 1450 to 1750, the symbol of our hatred was the witch. It seems unlikely that any of the people burnt or hung as witches were actually practicing witchcraft. They included midwives, healers, beer brewers, herbalists, pagans, single women, orphans, and widows.

Witches in art: T. H. Matteson, Examination of a Witch, 1853, Peabody Essex Museum, Essex, UK.

We believe without question that oxygen and gravity exist, even if we can’t “see” them – don’t we? In just the same way, our ancestors believed in the literal existence of demons and witches. The population genuinely believed that witches were souring milk, spoiling harvests, aborting babies, and stealing husbands. They were terrified that Satan himself walked among them. Women therefore became obvious scapegoats during a time of huge religious, political, and social upheaval. Witch hunts became a way for communities to express social tensions and existential fears during a time of profound social change.

Witches in art: Frans Francken the Younger, The Witches Sabbath, 1607, Kunsthistoriches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

The Reformation questioned the power of the Pope and the Church. This was followed by the Age of Enlightenment which turned Europe against much of the brutality of what we often call the Dark Ages. Fewer people believed in witches while the weight of evidence required for proving witchcraft meant fewer convictions. A healthy skepticism, increased literacy and social mobility meant that the supernatural could now be explained by rational minds as mere trickery and superstition.

Witches in art: Salvator Rosa, Witches At Their Incantations, 1646, National Gallery, London, UK.

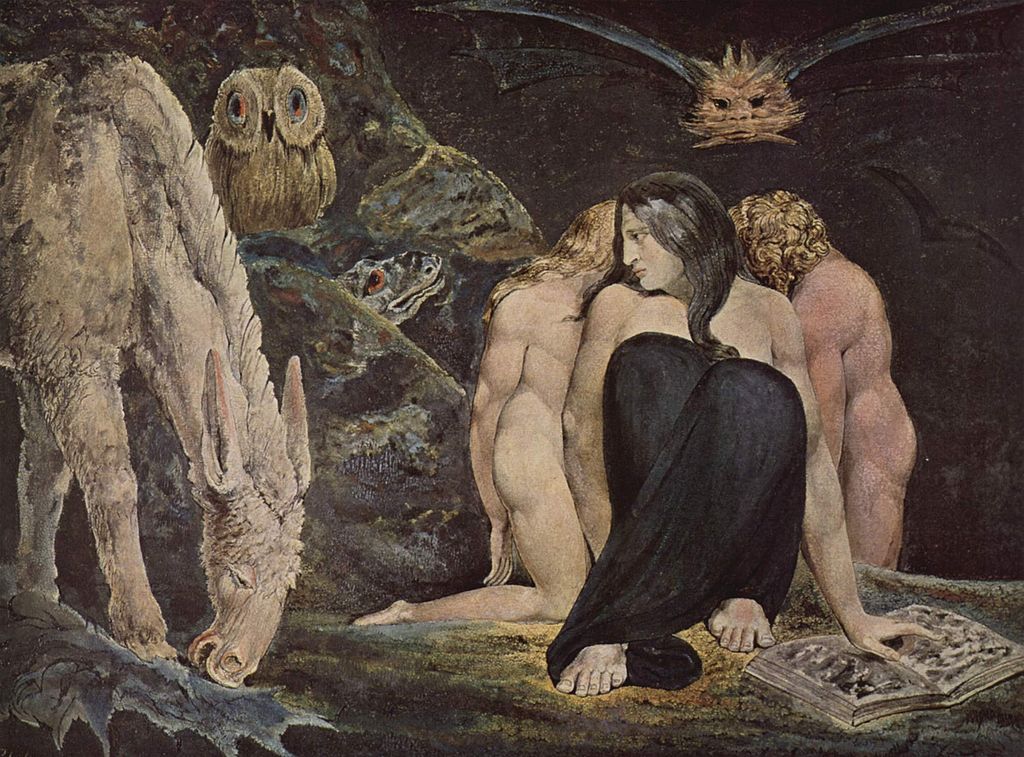

Although society, literature, and art may have mostly accepted witchcraft as a myth, witches retain their power as symbols and as representations of evil. “Double, double toil and trouble; Fire burn, and caldron bubble,” chant Shakespeare’s three witches in Macbeth. Representing evil, chaos, and conflict, Shakespeare’s witches popularized the image of a sisterhood of women, gathering around the cauldron. Witches gatherings (called a Sabbat) appear frequently in art, some fanciful, some fearful.

Witches in art: William Blake, Triple Hecate or The Night of Enitharmon’s Joy, 1795, Tate Gallery, London, UK.

Throughout the 19th century, we warned our children about the dangers of powerful women. Hansel and Gretel were almost eaten by the wicked and deformed woman living apart from society in the woods. The vain youth-obsessed queen of Snow White was equally scary. Witches were the baddies of Grimms’ Fairy Tales and still dominate many childhood story books and Disney films today.

Witches in art: Francisco Goya, Witches Flight, 1797, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Witches in art: Arthur Rackham, Hansel and Gretel, 1909, from The Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm, Constable and Co, London, UK. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Known for depicting feminine beauty and womanly mystery, the Pre-Raphaelites changed the image of witches by depicting them as priestesses or prophets. At this point in history, we see women from ancient mythology presented as powerful and attractive women. No longer a symbol to incite oppression and aggression, these witches are rather melancholic and thoughtful, although still performing their magic.

Witches in art: Frederick Sandys, Medea, 1866, Birmingham Museums, Birmingham, UK.

The rise of feminism and the emergence of Wicca (modern paganism) led to the witch being seen as a symbol of power. Here was a space where women could discuss issues such as persecution and exclusion across society. Increasingly, women were reclaiming the word – rather than an insult, they wanted ‘witch’ to be a signifier of power and agency. Witches were once a symbol of the oppression of a woman and her body. Women gathering together, with ritual, became about self-care, nurturing, and love.

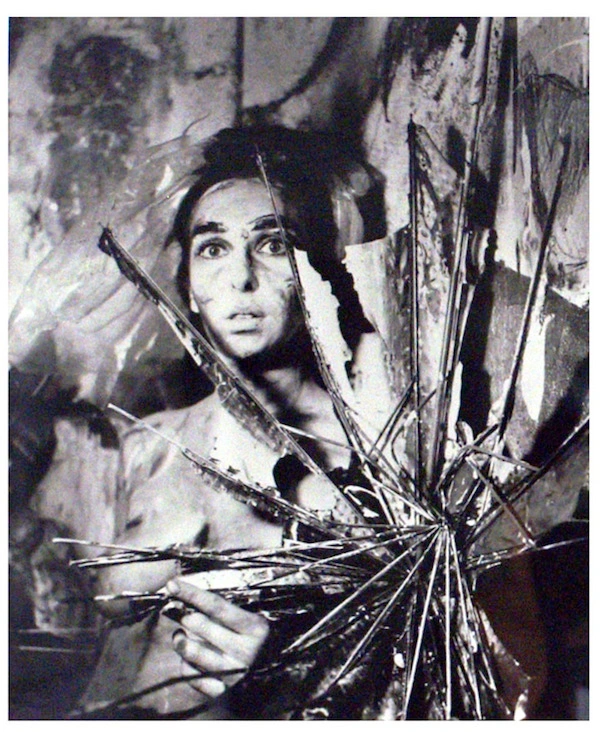

Witches in art: Carolee Schneeman, Eye Body no 24, 1963, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA.

Pop culture and television have given us so many characters and storylines involving witches. We had Sabrina the Teenage Witch and even a lesbian Wicca witch in Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Hermione Granger in The Harry Potter books and films gave us an image of witchcraft that was both clever and useful: “the brightest witch of her age”. In fine art however, witchcraft fell out of fashion and became rather kitsch. One such example is Andy Warhol‘s 1981 Witch, an image of the actress who played the Wicked Witch in the film The Wizard of Oz. Meanwhile some women such as artists Carolee Schneeman and Virginia Lee Montgomery experimented with the idea of a witch in a very thoughtful way.

Witches in art: Virginia Lee Montgomery, still image from Water Witching, performed in 2018 at Bard Hessel Museum of Art, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY, USA. Artist’s website.

Do not believe for a minute that witch hunts are over. Powerful women are often seen as lacking true femininity – they are the “nasty woman”. The current US Supreme Court holds misogynist views very similar to their 17th century witchfinder counterparts. In some parts of Africa, the Middle East, the South Pacific, and Asia, witch-hunting still occurs. Women and girls are imprisoned, tortured and killed. For example, in 2009, police in Saudi Arabia set up an “Anti-Witchcraft Unit” and in 2011, Amina Bint Abdul Halim Nassar was beheaded for allegedly practicing witchcraft.

Witches in art: The History of the Lancashire Witches, 1785, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Champaign, IL, USA.

Lawyer Claire Mitchell recently succeeded in obtaining a pardon and apology for those accused of witchcraft in Scotland. A national memorial is to follow. Mitchell states that she was emboldened by the #MeToo movement and wanted to address a historic injustice that resonates with women’s continued struggles against abuses today.

So, where do you stand? Some of you may have ancestors who were accused of witchcraft. If you had lived in the past, could you have been hunted down? Margaret Attwood’s dystopian novel The Handmaids Tale seems scarily prescient in these troubling times. Is the witch on the rise, and how will artists respond?

Witches in art: Virginia Lupu, Tin Tin Tin, 2018. Twitter.

If we’ve missed your favorite witchy work of art, let us know.

Also, you might be interested in Witches of Scotland campaign that seeks justice for those accused and convicted under the Witchcraft Act 1563-1736.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!