The Art of Science—Versailles at the Science Museum, London

Have you ever wondered how it would feel to witness the grandeur and opulence of the 18th-century French court? Then you might want to go to London.

Edoardo Cesarino 19 December 2024

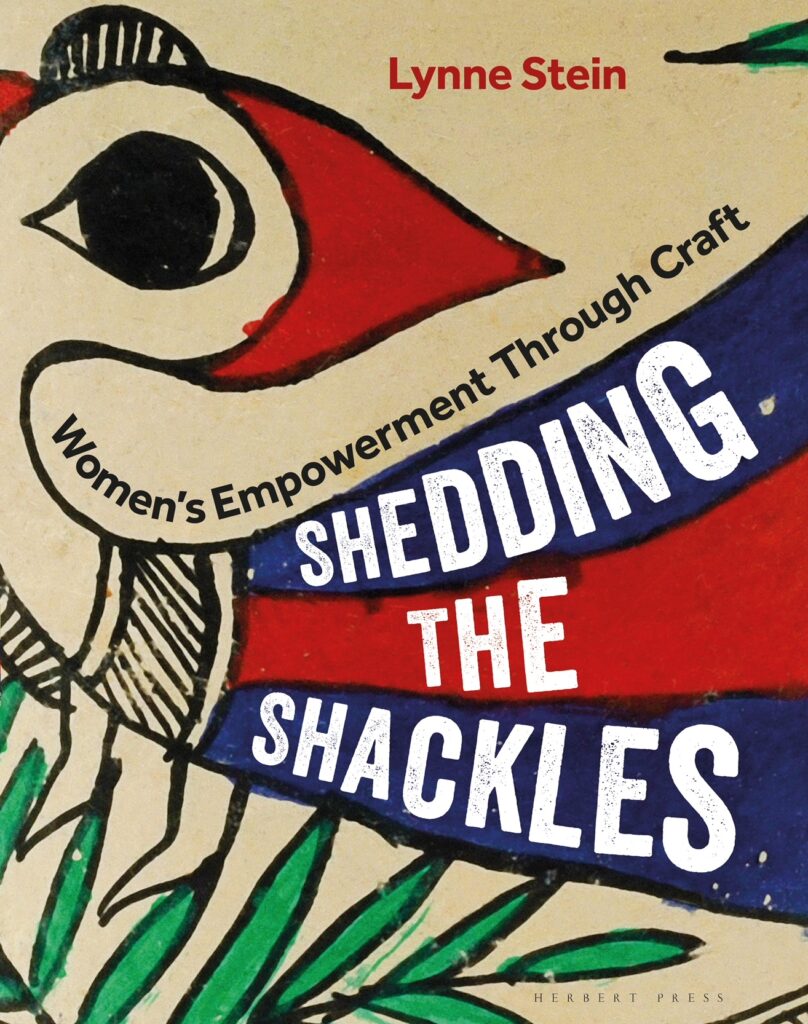

A review of Shedding The Shackles: Women’s Empowerment Through Craft by Lynne Stein, Herbert Press, Ireland, 2021. An exploration of crafting across the world, featuring artisans and craft initiatives.

Shedding The Shackles: Madhubani papier mache pencil pot. Photo by Robbie Wolfson.

This coffee table book is filled with sumptuous images of crafting from across the world. With textile artist Lynne Stein we travel the globe looking at women’s role in textile crafting. The book is divided into two parts. The first introduces us to groups preserving traditional practices. The second part is an exploration of a number of women’s craft initiatives.

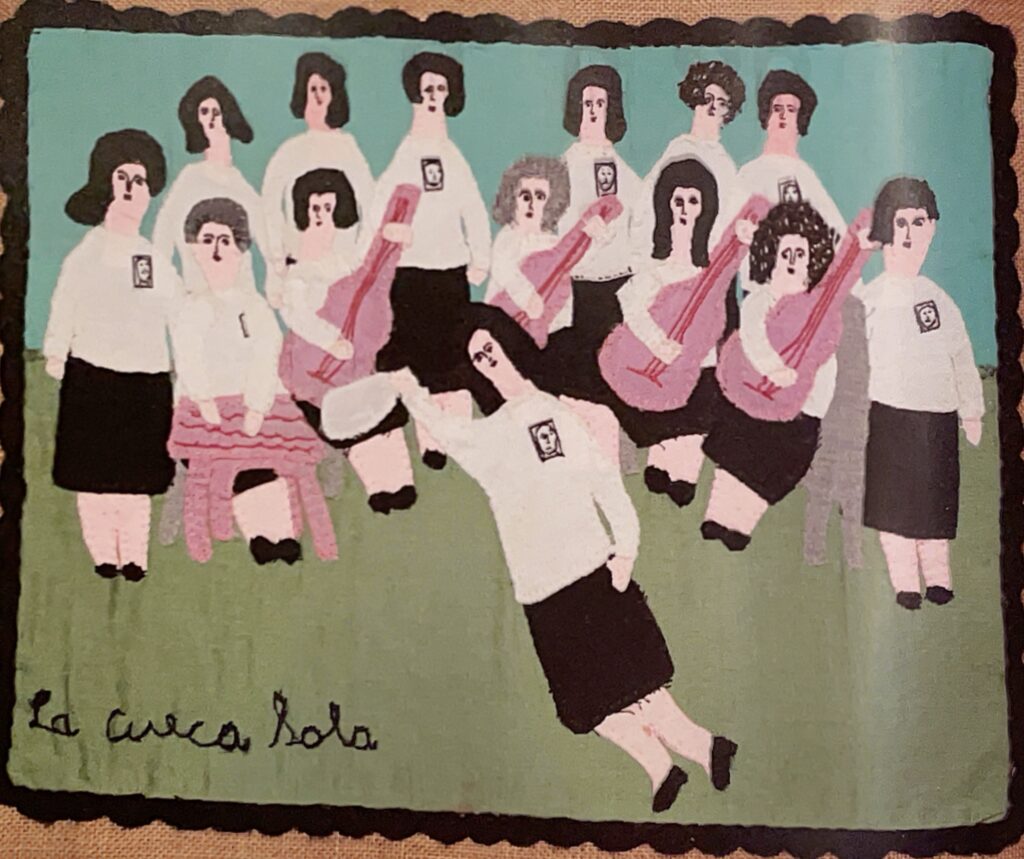

Shedding The Shackles: Gala Torres, La Cueca Sola, Conflict Textiles Collection, University of Ulster, Northern Ireland.

Stein gives us short narratives about the lives of the women she visits – we find out about their cultures and their textile traditions. Her investigations are personal and colourful, but not fleshed out enough – we get tantalizing glimpses of another life, another culture, but then we move swiftly on to the next continent.

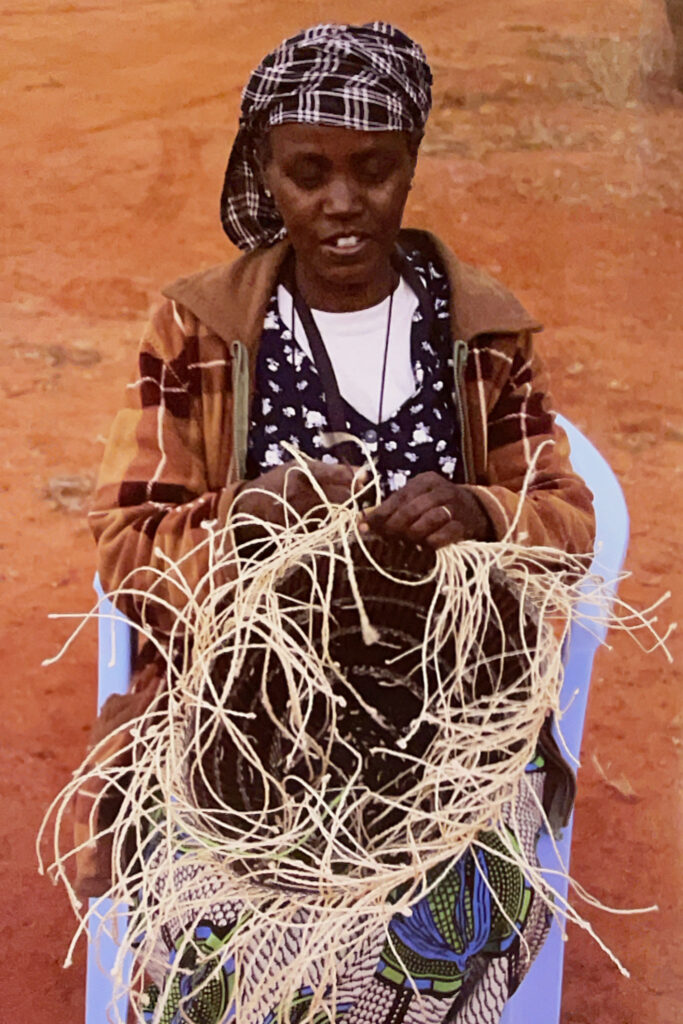

Shedding The Shackles: Kenyan sisal basket weaving. Photo by Lore Defrancq.

With each craft enterprise, Stein gives us a backstory and guides us through the history of the craft, how it has developed, and how it gets to market. Stein is passionate about the cultures she visits and shows us the potential for textile production to raise women out of poverty, whilst maintaining and celebrating their cultural histories.

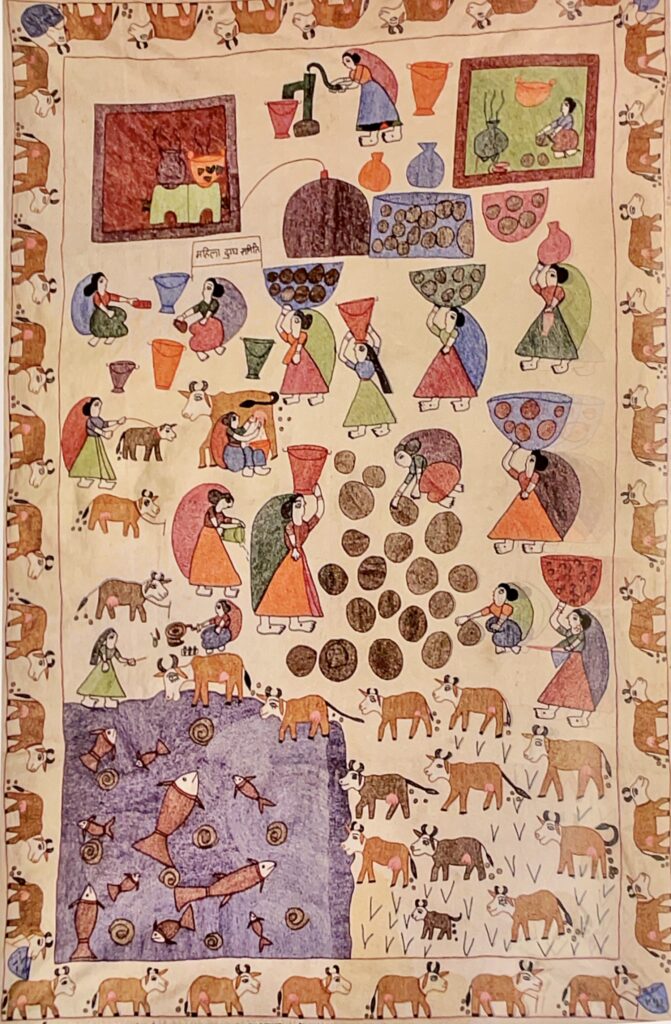

Shedding The Shackles: Nirmila Devi, Cow Dung Sujuni, 1999, Indian sujuni embroidery. Photo by Dr. Skye Morrison.

But of course, none of this is about art for art’s sake. Knitting thick woolen sweaters on wind-swept islands off the Baltic coast is a necessity for the women of the Kihnu. These are crafts born of need, with quite strict cultural traditions around the styles and colors that can be used.

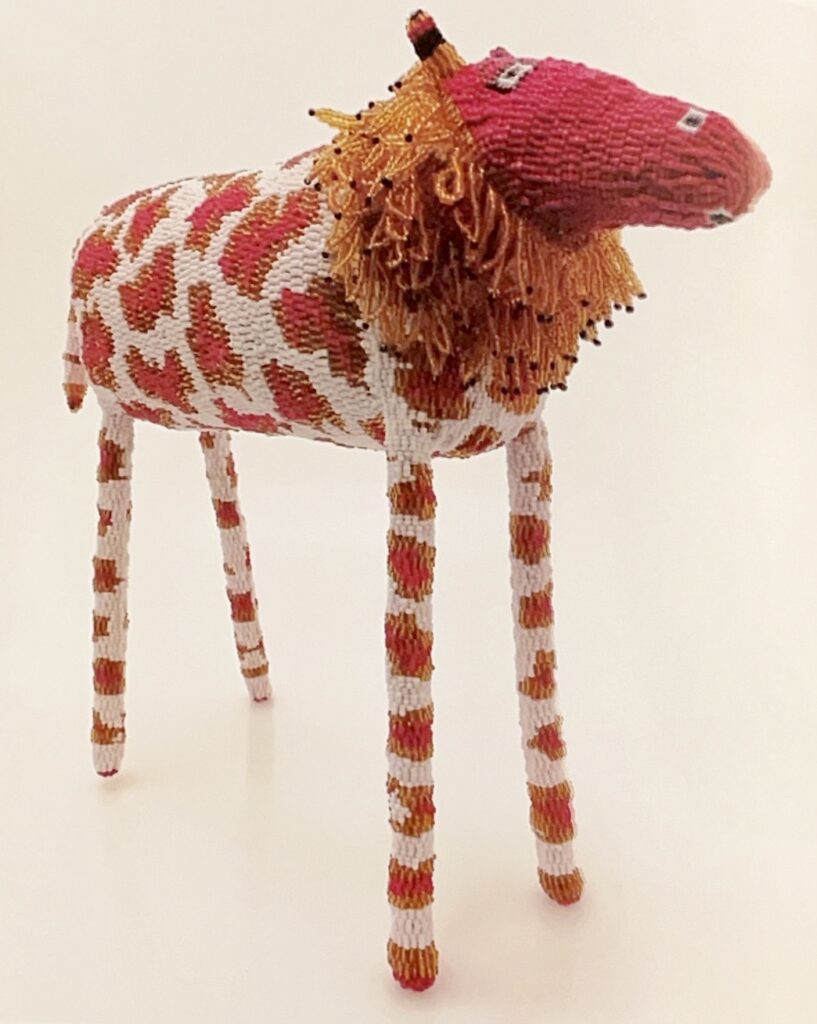

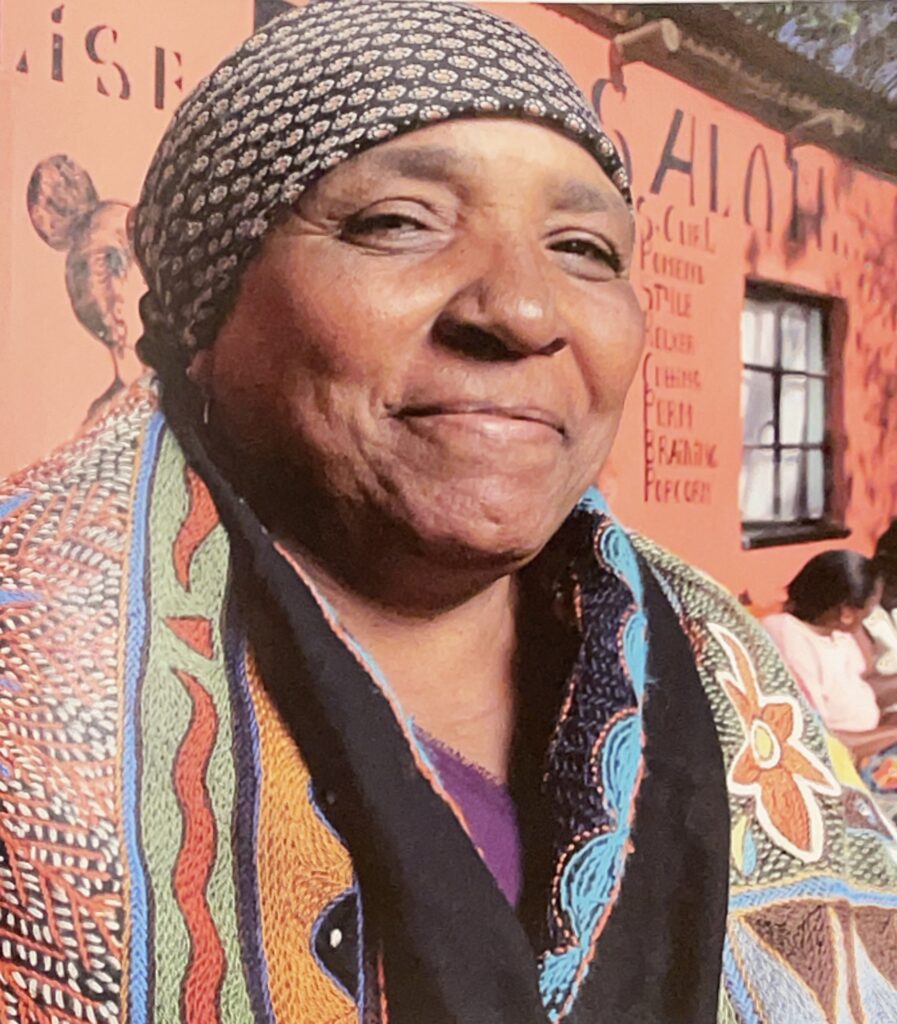

Shedding The Shackles: Monkeybiz beadwork, South Africa. Photo by Monkeybiz.

And let us not be mistaken, many of the women who produce crafts across the globe are cheated by middlemen, where the craft items move out of their hands and into the tourist market or the art market. In this situation the women’s payment is minuscule. The middlemen (and they are almost always men) take the big profits. At least here in this book, we can see successful stories of women joining co-operatives, fair-trade businesses, and social enterprises, with ethical business models that reward the maker as well as the seller.

Shedding The Shackles: PET Lamp Project, Colombia Esperara Sapidara. Photo by Studio Alvaro Catalan de Ocon.

One of the biggest projects discussed in the book is the PET Lamp Project, which reuses polyethylene terephthalate plastic bottles and containers, turning them into lampshades. This section of the book provides some fascinating political discussion points. On the one hand, we are producing mountains of plastic waste that need recycling. But should we be placing the responsibility for fixing that on the poorest communities on the planet? Are we outsourcing our problems again? Our leaders might be better suited to reducing the plastic waste in the first place. But in any case, beautiful lampshades are better than plastic-filled oceans.

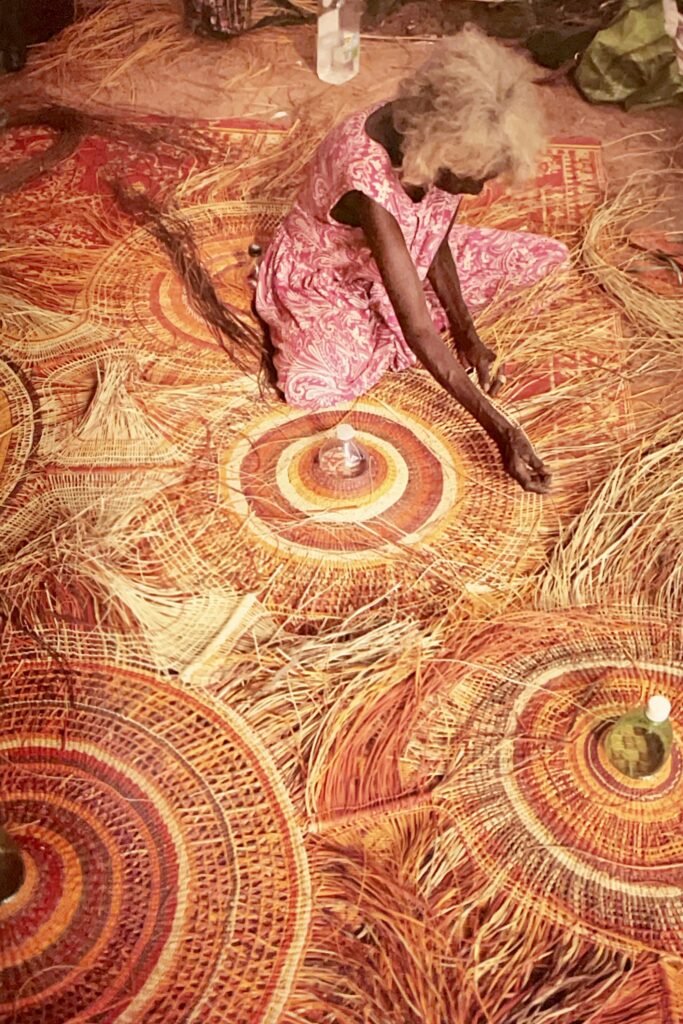

Shedding The Shackles: PET Lamp Project Australia. Photo by studio Alvaro Catalan de Ocon.

Slightly out of step with the rest of the book, it turns out that the PET Lamp Project was set up by three European men, the design is planned from Madrid, which is also where the lampshade molds are made. Is this the colonial mindset at work in a new environment? Men do the planning and the design, while the women do the dirty work? It’s not as simple as that, of course. This project has brought job security and a sense of renewed optimism to so many communities across the globe. We need male allies, helping to open doors that have been previously closed. And in their defense, the project does encourage communities to make the lampshades according to their own historical weaving and decorating practices, which means cultural memory and cultural pride are retained.

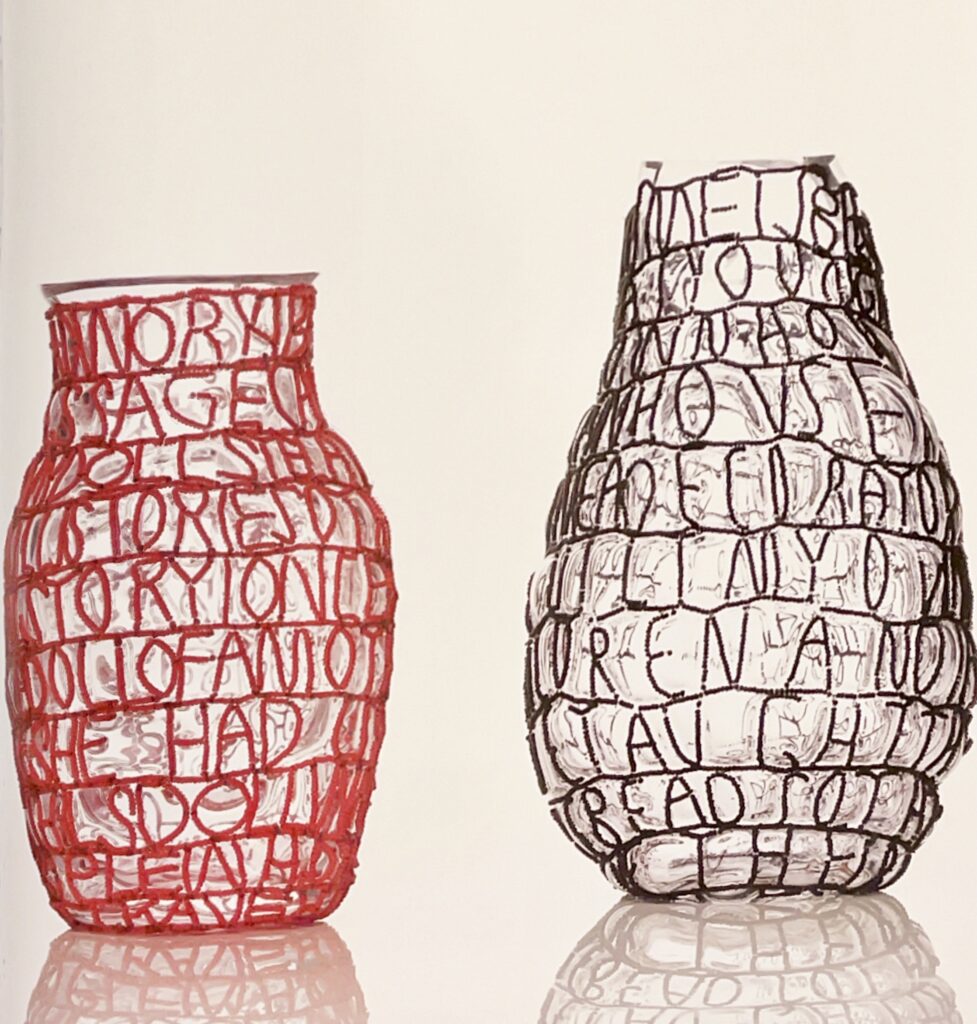

Shedding The Shackles: Siyazama Project + Front, Story Vase, South Africa. Photo by Anna Lonnnestan.

For most of the women in this book, crafting protects a tradition that ties them to their maternal ancestors. But those ties might also be oppressive when a woman lives in poverty and can barely feed her children with the income she makes from her work. Or if her work is simply a contribution to her dowry and her value on the marriage market. Globally, women and craft are still mostly seen as ‘not art’. And certainly, it does not have the values attributed to it that the average male Western visual artist might enjoy.

Shedding The Shackles: Kaross embroiderer with her creation. Photo Karosswerkers (pty) Ltd.

The pleasure many of the women take in their creative work is obvious. Their desire to contribute to their community is amazing. These women provide for their loved ones, but also pass down ancient traditions to the next generation. There is sometimes an uncomfortable feeling of the ‘great white savior’ coming in from the West and ‘helping’ these women sell their wares. But if they are paid low wages, how helpful is that? It is heartening to see how many of the outsiders involved in these crafting enterprises are offering mentoring plus assistance with technology and marketing, in the hope that the women eventually take on these roles for themselves.

Front book cover Shedding The Shackles: Women’s Empowerment Through Craft by Lynne Stein, Herbert Press, Ireland, 2021.

The stories which shed light on the power of craft to help with grief and trauma are very moving. The solace women take from creating work together is very much in evidence. For instance, the founding of Bosna Quilt Werkstatt. This collective offered community, care, diversion, and income to women whose lives had been shattered by the Bosnian War.

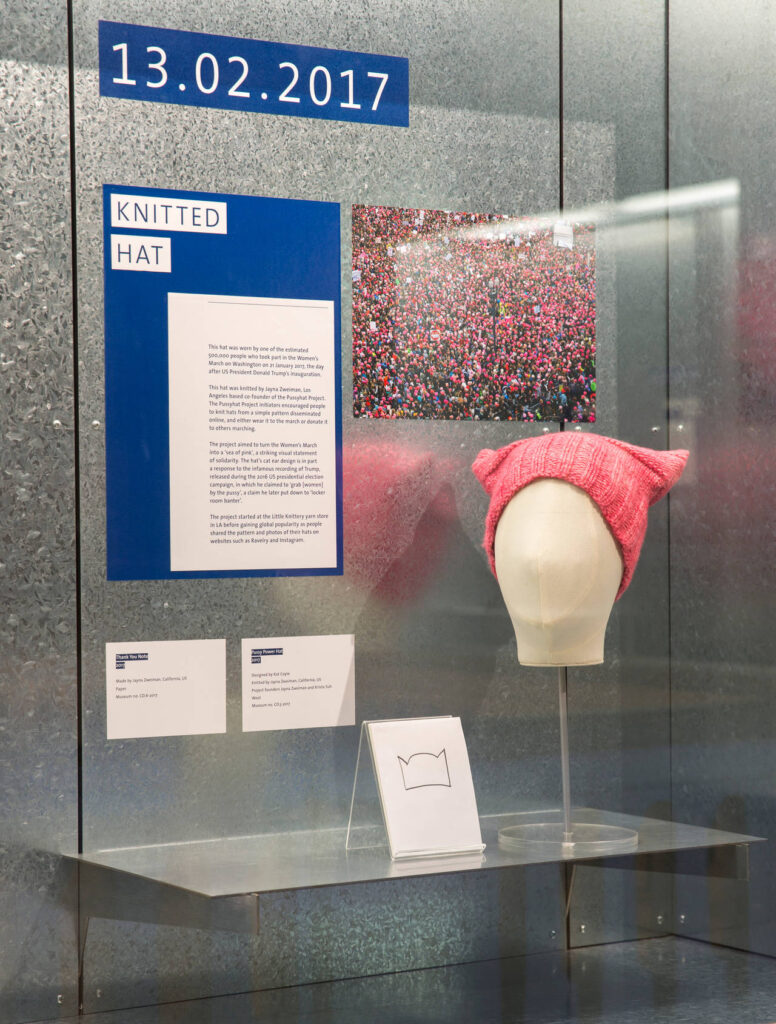

Shedding The Shackles: Pussyhat Project display, 2017, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

Stein does ask an exceedingly pertinent question in the book: Are shackles actually being shed? And if so, to what degree? Let us remember that some women in this book hand over their earnings to a man. Some work full-time as carers. Some still bow before male decision-makers. I agree with Stein’s summary that whilst women remain economically and socially disadvantaged, crafting can actually add to their burden rather than lessen it:

Amongst several cultures and societies, in addition to their various domestic tasks, the actual workload for women increases considerably, when adding the commercial practice of their craft into the mix.

L. Stein, Shedding The Shackles, p. 60.

However, we cannot, of course, deny the positive aspects of crafting, performed whenever and wherever:

At grassroots level, perhaps it is social cohesion, the sense of security derived from the ability to independently earn an income, and not least of all, the preservation, protection, and sometimes development of ancient, indigenous techniques which remain key factors.

L. Stein, Shedding The Shackles, p. 60.

Many of us have had experiences playing with fiber, yarn, and cloth. Whether making clothes for dollies or for ourselves, or through crafting at school, or working as crafters, it can provide solace, income, and pleasure. There is no doubt that crafting is an amazing journey, that any of us can join. Our contribution might be a small hand-sewn gift, or it might be world-changing. Remember the Pussy Hat Project of 2017? Thousands of American women standing against Trump’s misogyny and sexism. That sea of homemade pink hats on the Women’s March made front-page news across the world.

This would be a great book for a school library, or as a gift for a crafter. The photographs are an absolute joy, and anyone could spend a wonderful hour browsing this lovely book. Though for art historians it may not have the comprehensive indexing and timelines we are used to. The future for women who support their families through craft is by no means secure. Where next for the women crafters of the world? What we do about that is what NGOs and governments across the world must urgently address.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!