Turner and Constable: Rivals and Originals at Tate

Two of Britain’s most famous Romantic painters meet again in Tate Britain’s new exhibition. Turner & Constable: Rivals and Originals...

Sandra Juszczyk 8 December 2025

10 July 2025 min Read

The Women Who Changed Art Forever is a graphic novel written by Valentina Grande with the illustrations of Eva Rossetti. It’s a visual journey through the memories and artistic careers of four artists who made and developed the feminist art movement: Judy Chicago, Faith Ringgold, Ana Mendieta, and the Guerrilla Girls. These artists show us four different aspects of feminist art, from initial questioning of established taboos to the intersectionality of fourth-wave feminism. And above all, they defined themselves as feminist artists, choosing the hardest way so that, in the future, women and female artists could gain more and more visibility and keep the movement alive.

The Women Who Changed Art Forever brings readers directly into artists’ lives: we see their stories as a sequence of images and feel like we were in their heads as if we were part of their thoughts.

Empathy is one of the reading keys of this graphic novel and of feminism itself: being able to see the artist’s faces and memories adds an emotional value that lets the reader better understand their point of view. And this narrative method is also important because it makes the artists define themselves and not be described by an external gaze.

However, this book is not only these artists’ stories, but a collective account of a slowly changing society. These women’s lives intertwine with, inspire, or are inspired by those of other artists’ and intellectuals’, like Yoko Ono, Marina Abramovic, Cindy Sherman, Eleanor Antin, and many more who chose art as their means of struggle. This shows us that feminism is made by thousands of voices that fought, and are still fighting, to be heard.

It’s important to notice how Chicago, Ringgold, Mendieta, and Guerrilla Girls’ stories are connected: they all take place in New York during 1985, which is the year and place where Mendieta died and Guerrilla Girls started to act.

Let’s see how Grande and Rossetti introduce these artists and how they changed the art world forever.

The American artist Judy Chicago with one of her paintings on a car hood, 2015. Photograph by Donald Woodman. Wikimedia Commons.

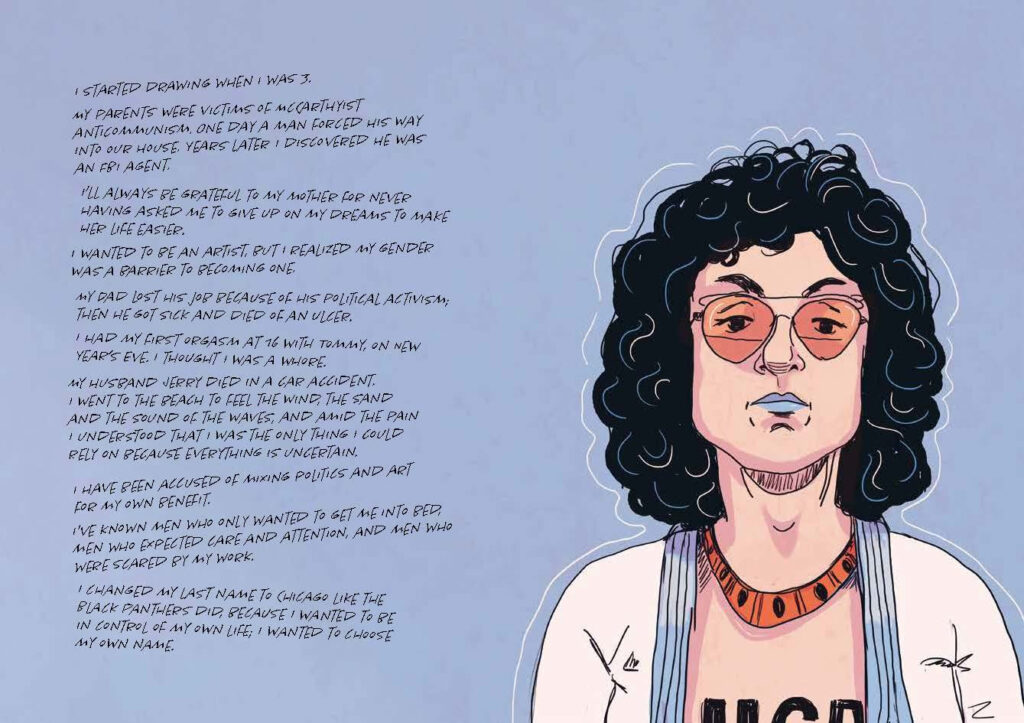

The part of the book dedicated to Judy Chicago starts with the artist introducing herself with a series of statements drawn on Through the Flower, her autobiography. From the first page, we see her defining herself with her words and in fact, self-determination is the leading theme of this story.

When she was young, she saw her father being persecuted because of his political activism, as they had defined him as a communist. Growing up, the artist understands the importance of the language we use and she changes her last name to Chicago like the Black Panthers did so that she could be in control of herself.

The Women Who Changed Art Forever: Feminist Art—The Graphic Novel, by Valentina Grande and Eva Rossetti, 2021, Lawrence King Publishing. Courtesy of Lawrence King Publishing. Page 16-17.

Chicago is a pioneer of the feminist art movement, and as one of the first feminist artists, she decides to work on language, to reclaim it. Indeed, her career is made by her responses to the people who tried to define her and her art. Having experienced the rejection of curators and gallerists who had refused to show her work because of her gender, in Fresno she starts the first feminist art program, pushing women to be aware of their desires and to speak up for themselves.

Her art too was born from her reactions to the external gaze and definition of women’s bodies. That’s why she works on the de-stigmatization of taboos, which are not part of who we are, but are instilled in us while we grow up. They tell us that we can’t show or even talk about some parts of our bodies as if they were unmentionable and that we should be ashamed of them, thus making women grow up with a deep sense of shame and guilt.

Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, Virginia Woolf’s ceramic plate, 1979, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Brooklyn, NY, USA. Photograph by Bee1120 via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

In this way, women’s bodies are the property of someone else. With her art, Judy Chicago makes a political choice and lets us be the owners of our bodies. The graphic novel takes two of her artworks to explain the concept of reappropriation of the language and the female body: The Dinner Party, a series of ceramic plates that represent as flowers the vaginas of important women forgotten by history, and Red Flag, a photo of a tampon coming out of a vagina.

It’s no coincidence that her story ends with a memory of her father making her understand what being authentic means, telling her something that has inspired all of his life and artistic path: we can take the words other people used to define us and give them a different meaning so that we can determine ourselves.

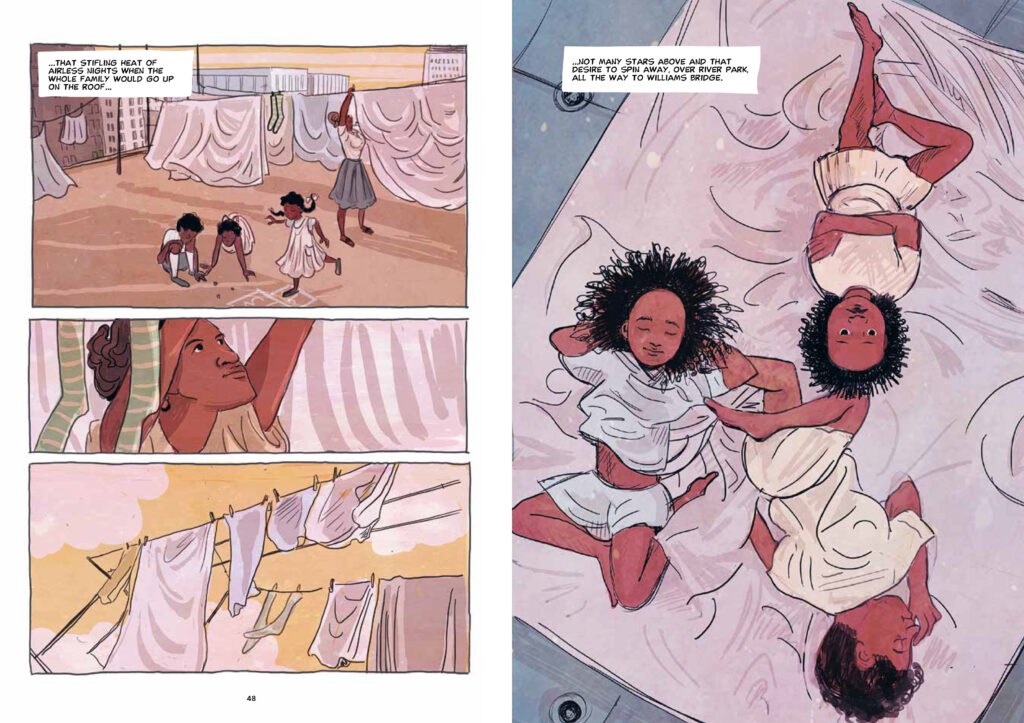

The structure of Ringgold’s story is similar to Chicago’s: first, the authors inform the readers about her background and early life, based on her autobiography, We Flew Over the Bridge, and then readers can be part of her thoughts and memories during her walk.

But with Ringgold, we go a step further into the development of the feminist art movement: she is an African-American woman whose family history is linked to the enslavement of African people in America. With her art and activism, she starts fighting for Black women’s rights.

The Women Who Changed Art Forever: Feminist Art—The Graphic Novel, by Valentina Grande and Eva Rossetti, 2021, Lawrence King Publishing. Courtesy of Lawrence King Publishing. Page 48-49.

When she understands the pain her ancestors went through, she chooses story quilts as her art form instead of oil paintings. Quilt-making was historically considered a minor art because it was done by female slaves: it was the only artistic practice they could perform, and just because their products could then be sold. Those quilts were the representation of the stories of African people who tried to escape slavery.

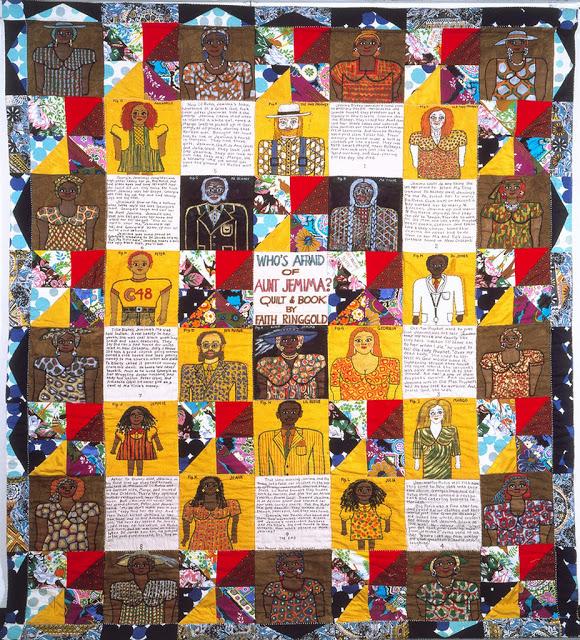

Ringgold’s first story quilt, Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima?, criticizes the American myth of the southern female slave, Aunt Jemima. The artist freed Aunt Jemima from the myth, transforming her into a real African-American woman who takes control of her life.

Faith Ringgold, Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima?, 1983. VoCa.

The historical context is very important for this artist’s story: history greatly influences her art, which is a means of social development for her.

In 1960, the artist joined her first protest which aimed to include Black artists in contemporary art exhibitions: the curators decide to open up to a dialogue with the protestors, but only with the male ones. Soon she understands that at that time fighting for Black people meant fighting for Black men and that feminism was made by and for middle-class white women only. Black women were invisible to society, so her activism becomes the way to assure her existence too.

Here, we see the first steps of the feminist art movement towards intersectionality, and this concept is well-represented by the end the authors chose for Ringgold’s story: we find a story quilt that contains the images of all the artists and people mentioned in the previous pages. They were united by the same desire for equity, but they didn’t know it yet.

Ringgold thus tells us to accept and be proud of the complexity of our identities, bringing us to Ana Mendieta’s artistic search for the plurality of our identities.

Ana Mendieta, The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Galerie Lelong, New York, NY, USA.

Ana Mendieta’s art is based on two themes that are tightly tied to her past: origin and identity. When she was 12, she had to emigrate from Cuba to the United States with her sister, with Operation Peter Pan.

Since then, she had always felt a need to come back to her motherland, which she identifies as the Great Mother, the universal energy that pre-Indo-European people celebrated as the origin of all things. With her series Siluetas she finds her roots in every landscape she goes through, imprinting her body on the soil. Her artwork then vanishes with natural elements like water and wind, emphasizing the ephemerality of the materials she uses. She doesn’t impose herself on nature but becomes part of it in a fluid cycle of death and re-birth.

Photographs from Ana Mendieta’s Siluetas series. Sleek Mag.

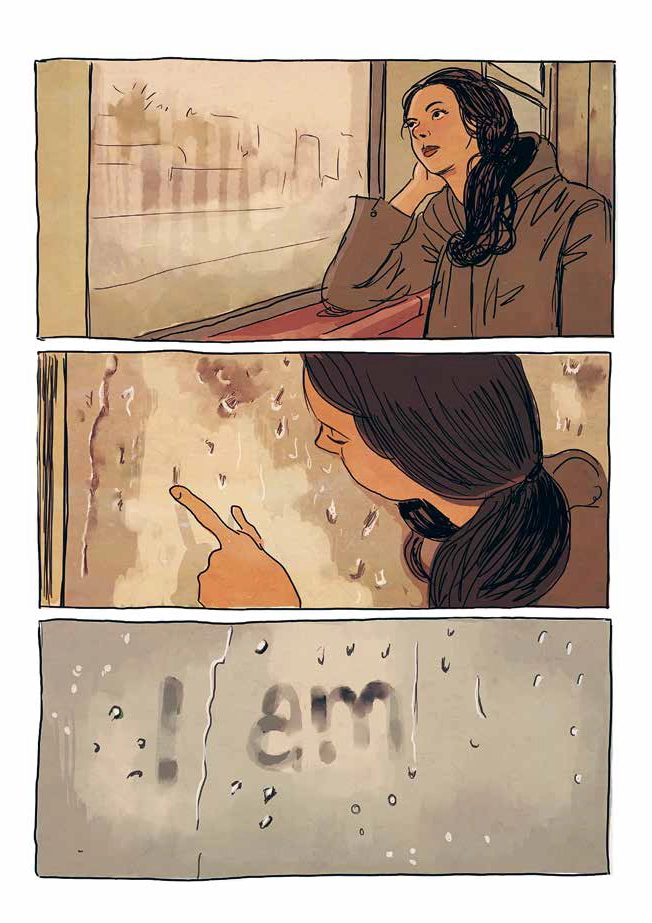

Her art, as her identity, can’t be easily described: it’s a combination of performance art, body art, land art, photography, video art, and sculpture. Mendieta seeks freedom, being all the versions of herself she believes exist, and challenging the binary patriarchal system. She thinks that identity consists of the multiple possibilities of our personality and the self and that we can describe ourselves in various ways through words, images, and actions.

At one point, in the graphic novel, she wonders:

above and beyond any color, any sense of belonging, any gender… how many identities are there within us?

This is a very important topic that Gender Studies was developing in those years, defining gender as a performative repetition of a series of actions associated with the male or female. Ana Mendieta urges the feminist art movement to understand that identity goes beyond the social structures we are born with; it is fluid and can be determined by ourselves.

The Women Who Changed Art Forever: Feminist Art—The Graphic Novel by Valentina Grande and Eva Rossetti, 2021, Lawrence King Publishing. Courtesy of Lawrence King Publishing. Page 79.

Mendieta died in 1985, falling from the balcony of her apartment. She was 36 years old and in the prime of her artistic career. Her husband, the sculptor Carl Andre, was put on murder trial; that night, one of their neighbors had heard the couple arguing and Mendieta screaming “No” right before she fell. But he was acquitted owing to a lack of evidence in 1988.

Since then, the art world has split in half: some artists took Andre’s side, even testifying on his behalf at the trial; while others were sure that he was the cause of Mendieta’s death and kept protesting against his absolution. These protests continue even today at Andre’s exhibitions, after 36 years, both to remember the artist and to boycott Andre’s work, as Mendieta’s death is not an isolated case but represents the endpoint of patriarchal culture. This is something that the artist had always spoken out against, since her first artworks.

The authors decided not to mention this part of Mendieta’s story and not to call her husband by his name, as the book aims to tell the story of her life and art.

Guerrilla Girls are very important in Mendieta’s story. They start putting up their posters in 1985 in New York, and in 1992, they founded the movement WHEREISANAMENDIETA, mobilizing the first protesters with the Women’s Action Coalition.

Guerrilla Girls, What Do These Men Have in Common?, 1995. Guerrilla Girls.

While Ana Mendieta wanted to express her multifaceted identity through art, the Guerrilla Girls sacrifice their names and faces to represent every person oppressed by the patriarchal system, regardless of their gender or origin. They ironically challenge the established art system by putting up posters that condemn the hypocrisy of museums and galleries which exclude every non-white-male-cis-hetero artist.

Through the years, they have expanded in every part of the world and are still supporting every human right. They are the last step (for now) of the movement: they represent intersectional feminism, which includes everything Chicago, Ringgold, Mendieta, and any other feminist artist ever fought for.

The Women Who Changed Art Forever: Feminist Art—The Graphic Novel by Valentina Grande and Eva Rossetti, 2021, Lawrence King Publishing. Courtesy of Lawrence King Publishing. Page 102-103.

Renato Poggioli in The Theory of the Avant-Garde describes the differences between the terms “school” and “movement”, explaining the opposition between the academic art and the new art forms that developed between the end of the 19th and 20th centuries.

The definition of “movement” also applies to the feminist art movement: it is a dynamic concept that keeps evolving and works against tradition and the accepted authorities. That’s why The Women Who Changed Art Forever tells us that the feminist art movement is not over yet and it probably will go on and on, transforming itself, until the established system changes and people in every part of the world are free to be whoever they want:

The lowest rung of the privilege ladder would be reserved for a disabled, Black, trans, lesbian migrant woman. Does such a person exist? Of course they do, but they are invisible. The Guerrilla Girls and all feminist artists work to ensure that person can represent themselves – and no one need wonder whether they exist anymore.

Foreword in The Women Who Changed Art Forever, Laurence King Publishing 2021.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!