5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

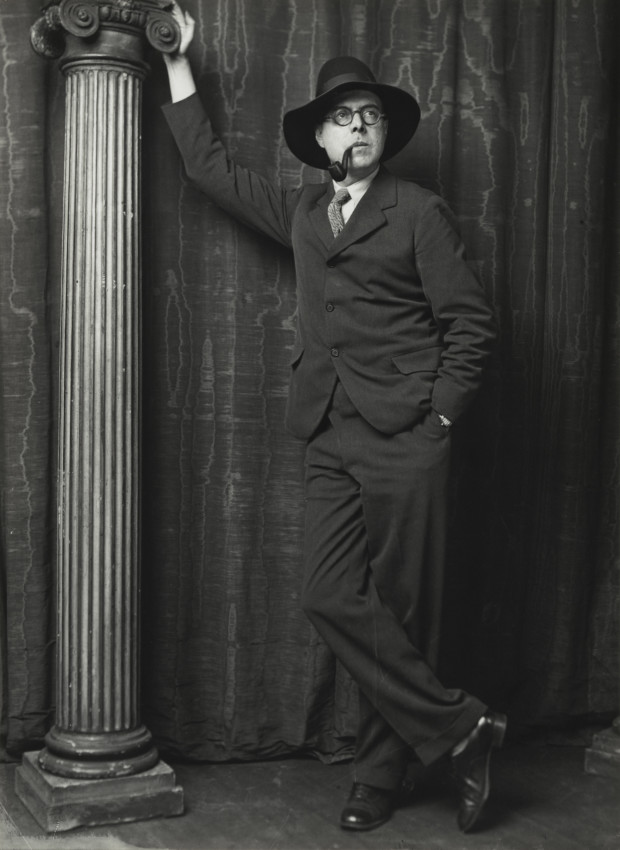

“Vorticism, in fact, was what I, personally, did and said at a certain period”. These are the words of the 20th century’s most spoiled, narcissist visionary, Percy Wyndham Lewis. He described himself as a “novelist, painter, sculptor, philosopher, draughtsman, critic, politician, journalist, essayist, pamphleteer”. He was the founder of a new art movement called Vorticism, a rival to Futurism in Italy, that exploded onto the British Art scene in the first half of the 20th century.

In the original Vorticist manifesto of 1913, Lewis placed his name alongside a group of artists that included William Roberts, Henri Gaudier Brzeska, Edward Wadsworth, Jessica Dismore, and Helen Sanders. But who was this man who antagonized all that he came up against? Of himself Lewis said:

I have been called a Rogue Elephant, a Cannibal Shark, and a crocodile. I am none the worse. I remain a caged, and rather sardonic, lion, in a particularly contemptible and ill-run zoo.

Percy Wyndham Lewis, Blasting and Bombardiering, London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1937.

The story of Lewis’ birth varied depending on who he was talking to. Allegedly born on a yacht off the Nova Scotia coastline in 1882, when in reality he was born on land. His father, an American who fought on the Union side in the American Civil War and his mother, an Englishwoman, separated when Lewis was 11 and he was sent to a preparatory school in Rugby.

Lewis studied at the Slade School of Art in London from 1898 and was a contemporary of Augustus John and William Rothenstein. Three years later, he moved to Paris where, after discovering Cubism and Expressionism, he created a new movement – Vorticism.

As Lewis was known for his arrogance, it is not surprising that he claimed himself to be the only founder of Vorticism. His abrasive personality meant that he rarely maintained friendships and collaborations for a long time. A founder of the Camden Town Group in 1911, Lewis exhibited at Roger Fry’s Post-Impressionist Exhibition of 1912 which brought him into the Omega Workshop. Later, Lewis fell out with Fry and the rest of the Omega group and it was at this point that he began the Rebel Art Group with artist and financial backer, Kate Lechmere and other artists who then formed the core of the Vorticist movement.

Kate Lechmere was more than a muse and partner; the two were romantically involved until Lechmere met the philosopher and critic, Thomas Ernest Hulme, a bluff, physically intimidating Yorkshire man to whom she became quickly engaged. Lechmere said that once there was an argument between her and Lewis over Hulme. Afterward, Lewis went racing off to confront his love rival. Unfortunately for him, Hulme was stronger and, according to the story, ended up hanging Lewis upside down off tall iron railings.

The 1912 painting of Lechmere, entitled Smiling Woman Ascending a Stair, shows Lewis’s Cubist interests. The figure is depicted with geometric shapes and we can recognize its deep grin from other works by Lewis. For Lewis, it was Lechmere’s outstanding feature. In a Daily Mail interview, Lewis said of the work:

That picture is a Laugh though rather a staid and traditional explosion. The body is a pedestal for the laugh.

Percy Wyndham Lewis, Daily Mail.

In December of 1913, the leader of the Futurist movement, Marinetti, met Lewis. From this moment, Lewis and his fellow artists embraced modernity and the machine age within their art, but with a British twist. Like Futurism, this new movement delivered a manifesto in which they stated their desire to reject the romanticism of a bygone age, and instead, celebrate “the forms of machinery, Factories, new and vaster buildings, bridges and works”.

In this, Lewis’ first Vorticist canvas from 1915 entitled The Crowd, he reduces the cityscape of factories and office blocks to a schematic composition in which basic pictorial representation of tiny, red workers congregate, pushing against one another, filling spaces, creating the mass of workers that the new factories were churning out. Two sets of figures carry differing flags, perhaps signifying the warring political parties. As Lewis originally named this painting Revolution, it is an entirely possible interpretation.

The war that has been desired by the Futurists finally erupted onto the world’s stage on Sunday, August 4, 1914. In the Vorticist magazine, BLAST, Lewis and his fellow Vorticists called for elements of our society to be “blasted”, while others were to be blessed. This did not stop Lewis from being a part of this “war to end all wars”. He enlisted in 1916 as a gunner and then as a bombardier in the Garrison Artillery, arriving at the battlefields of France in 1917, where, after the Ypres campaign, he became one of the official war artists.

Lewis painted A Battery Shelled for the British in 1919 and it is his most famous work.

In the 1992 catalogue for Art and War, Angela Weight Keeper wrote about the figures that Lewis drew in his war painting:

The iron-muscled figures in his First World War drawings strive fiercely at their tasks, pulling, dragging, plotting, surveying, laying, digging, loading, firing while explosions erupt all around.

Angela Weight Keeper, Art and War, exhibition catalogue, 1992.

The officers watch as the insect-like lower ranks enact all of these actions. The reduced form of the soldiers can almost be connected to the actors in The Crowd – ordinary, faceless workers being conscripted into the faceless army, desperately fighting a recognized enemy.

The landscape is being destroyed as we and the three army personnel look on; their calm stance contrasting with the business of the soldiers working through these horrific circumstances. However, Lewis is not sentimental in his depiction; here is a man who observes and comments but does not allow himself to be influenced by the emotional response that other artists used at this time.

Throughout his career, Wyndham Lewis continued to challenge and argue his way through the decades of change. His unflattering portraits and his metaphysical canvases remained a passion. Even when he was losing his sight due to a tumor, Lewis continued to show you what a grand visual legacy a person can be responsible for if they submit themselves to proper training at the start, and are not driven about by wars and otherwise interfered with.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!