Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

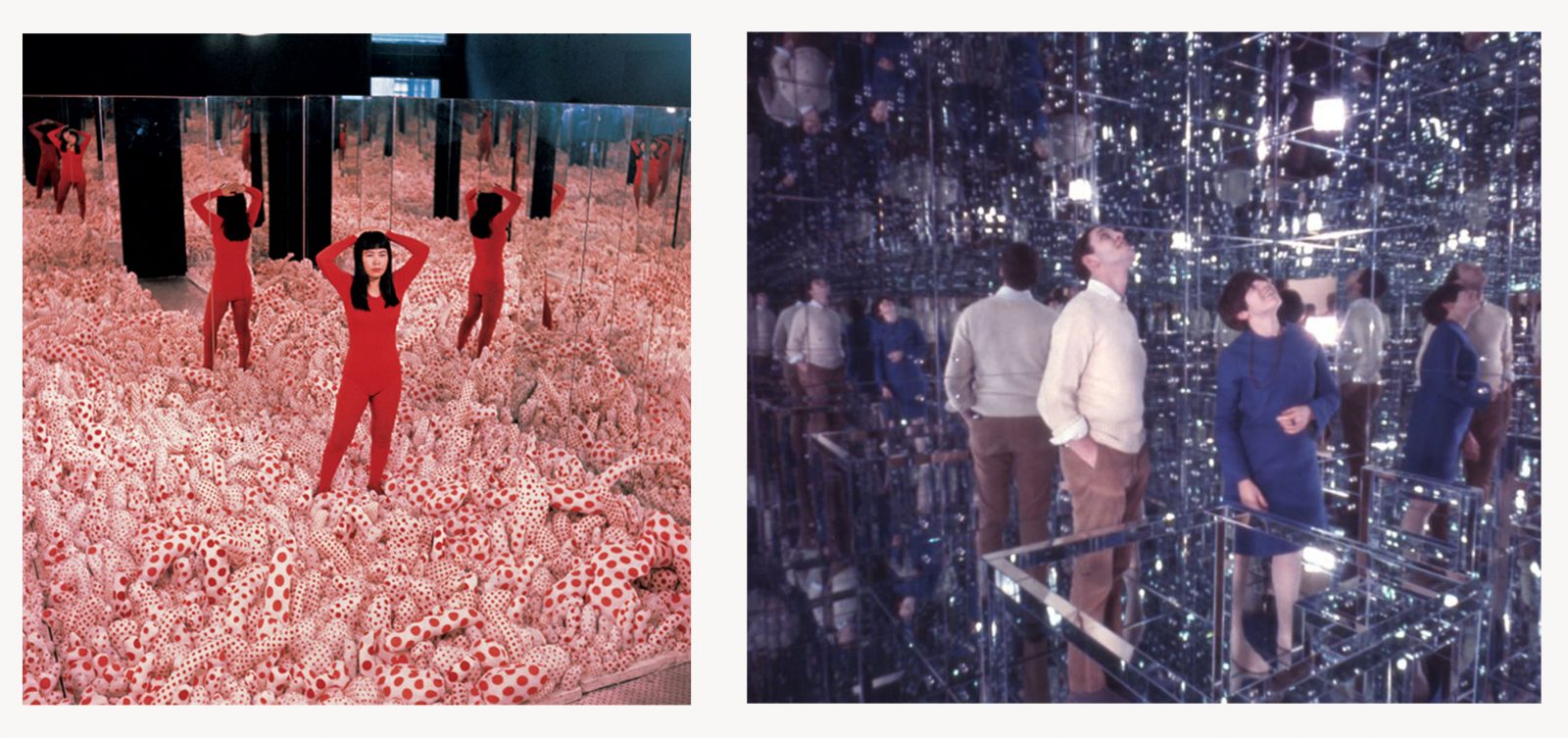

Internationally renowned, Yayoi Kusama is famous for her use of polka dots, and her immersive installations. Active since the late 1950s, she has had an incredibly long career. Her immense legacy even transcends the borders of the art world. Yet, in 1955 “the princess of polka dots” was an unknown young Japanese woman only dreaming of becoming an artist. Looking for a way to succeed, she sought advice from one of the greatest artists of her time: Georgia O’Keeffe. Discover how Yayoi Kusama’s and Georgia O’Keeffe’s lives are intertwined.

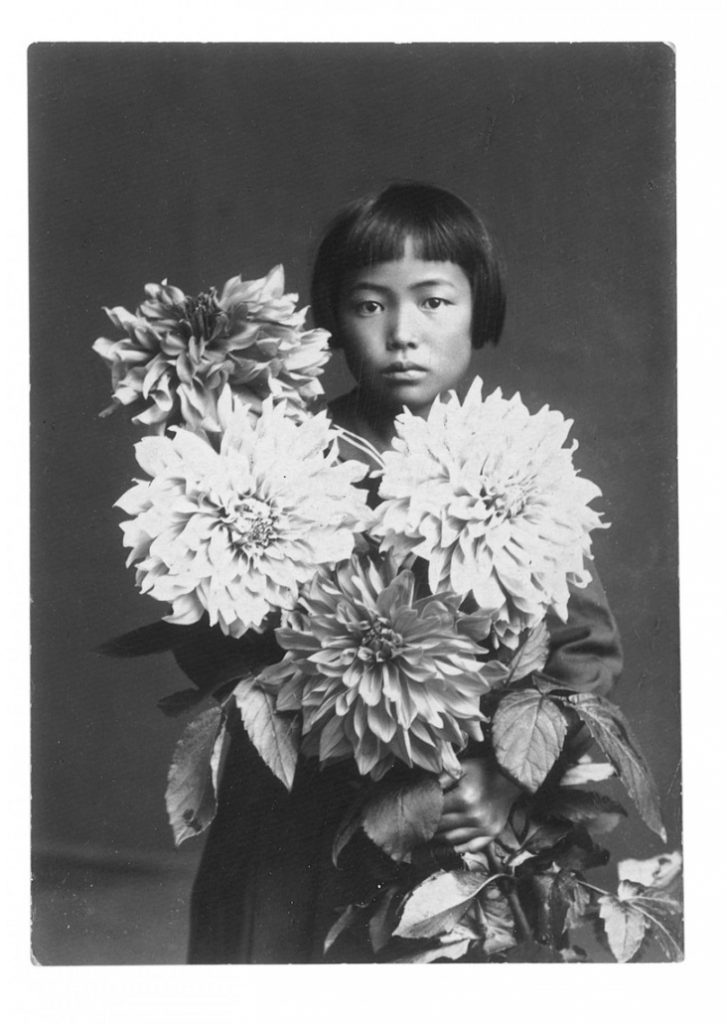

The youngest child of a seed merchant family, Yayoi Kusama is a native from the provincial city of Matsumoto in Japan. She grew up in a dysfunctional household. Her mother forced her to spy on her unfaithful dad and would beat her up out of rage. Still a little girl, she began to make art after a psychotic event in the family’s fields of violets.

Afraid of her recurrent hallucinations at first, Kusama started to embrace them. Drawing was a way to escape and to break free from her anxieties.

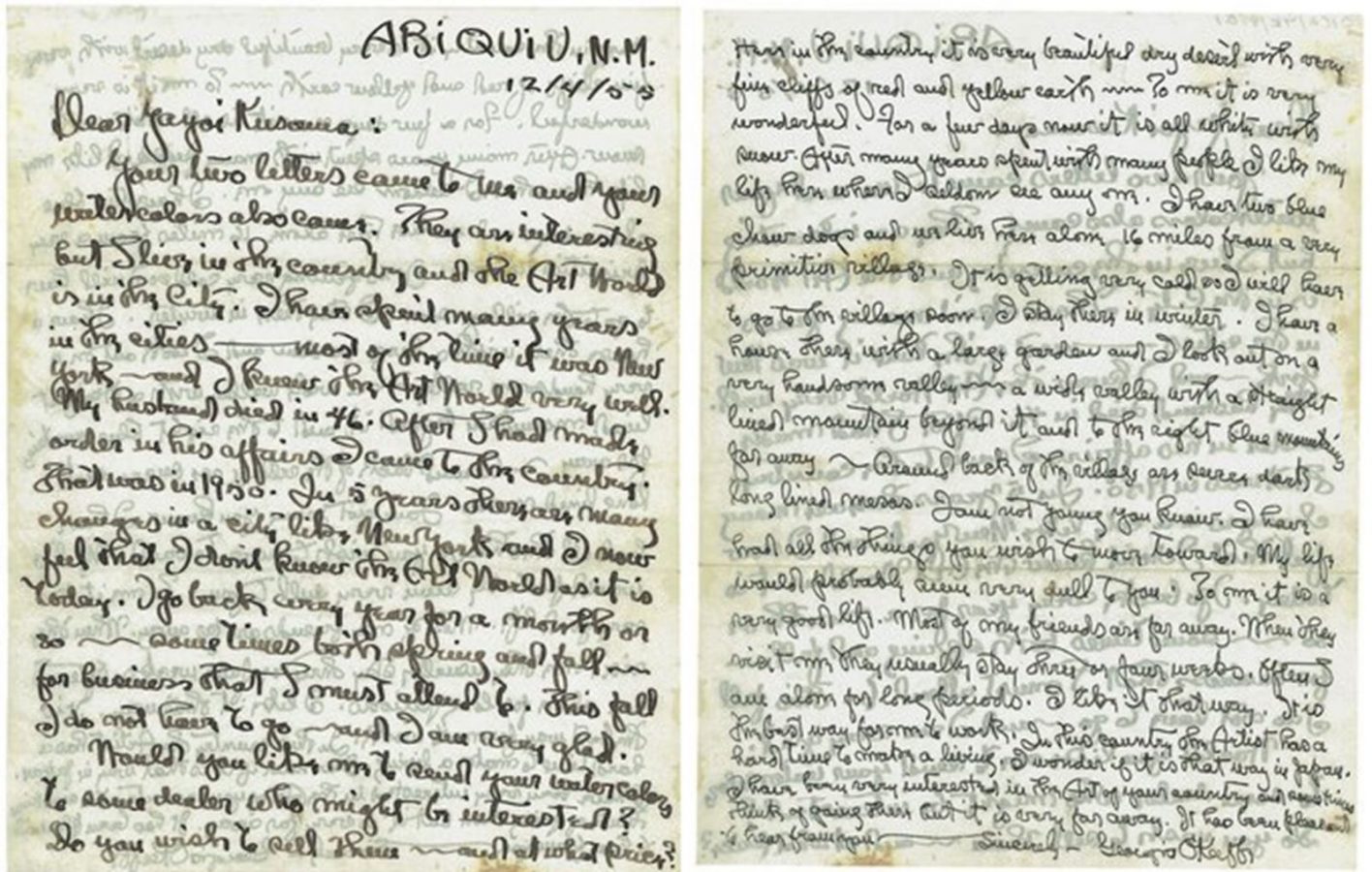

Far from considering her practice as a hobby, the blossoming Kusama decided she would become an artist. Against her family’s will, she went to an art school in Kyoto to learn painting. She didn’t stay there as the traditional setting of the education didn’t suit her. Kusama had bigger projects. She dreamed of being as famous as the American artists she saw in the books she read. She discovered Georgia O’Keeffe in one of those books. Impressed by O’Keeffe’s paintings as much as her accomplishments as a woman, Kusama decided to write to her.

To Kusama’s surprise, O’Keeffe responded. Not without warning of the difficulty of choosing such a path, she advised Kusama to go to New York and show her work “to anyone […] interested”. In the documentary retracing Kusama’s career, the artist declares O’Keeffe’s response gave her the courage to leave Japan for the United States to pursue her vocation.

Yayoi Kusama’s career would have taken a radically different trajectory if she hadn’t had the courage to write to Georgia O’Keeffe. At best, she would have fallen under the category of Outsider Art, as happens to those who are not lucky enough to find the right person to endorse them. In the worst case scenario, the despotism of her mother in a “too feudalistic” Japan according to the artist’s own words, would have crushed her creative energy.

Although Yayoi Kusama engaged in correspondence with Georgia O’Keeffe, the two didn’t develop the usual mentoring relationship.

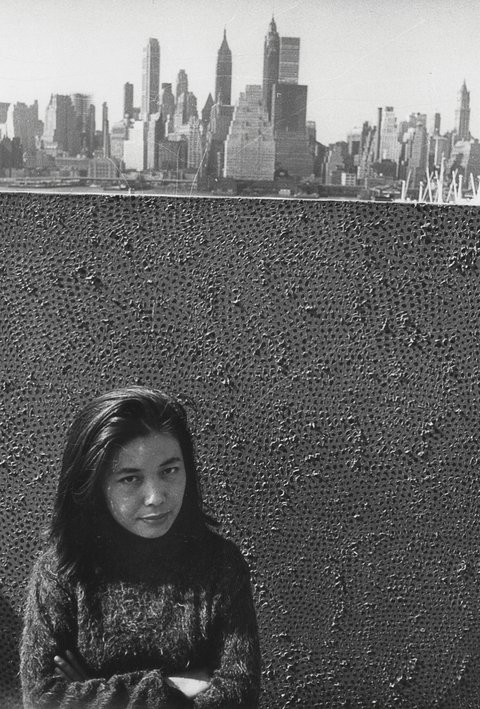

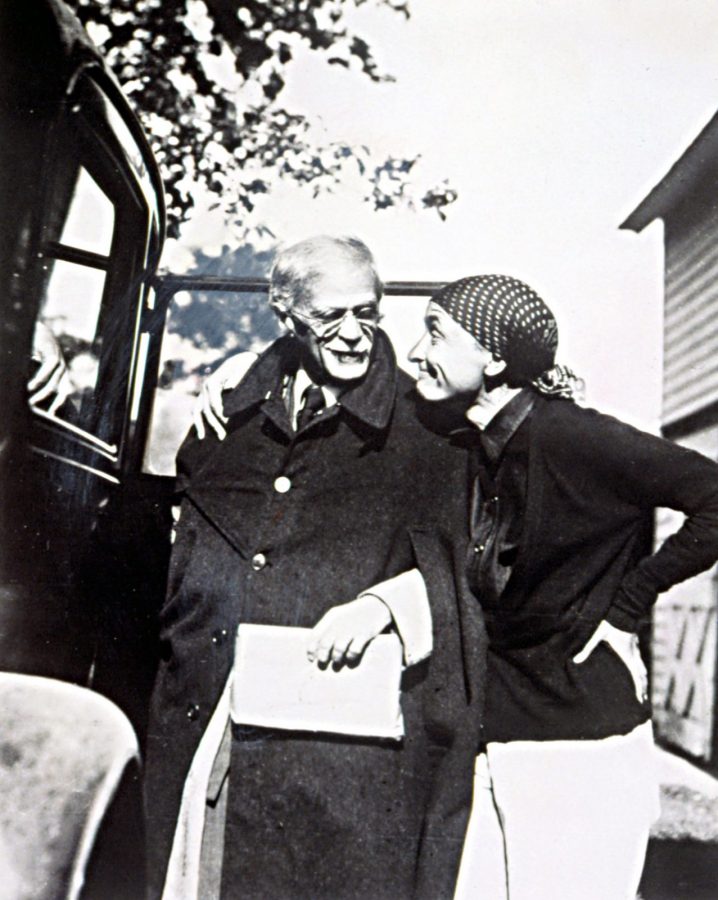

When Yayoi Kusama arrived in New York in 1958, O’Keeffe was living nearly 2000 miles further west, in New Mexico. Their relationship didn’t go further than a meager correspondence and only one short meeting. In an article for Tate, Yayoi Kusama shares little details of this encounter. She develops more about what the impression of seeing her role model made on her rather than anything else. There is a restraint in Kusama concerning her private life, which is a quality found in O’Keeffe as well.

The two women knew and respected each other’s work but they kept their exchanges formal.

In a traditional mentorship, experienced artists take younger talents under their wings. Masters teach pupils everything they need to be successful in their turn. This practice has been going on for centuries. It allows a special, if not intimate, relationship to be established between the mentor and the pupil. It also develops competitiveness, as the student is predestined to surpass the master. This is how it went for Georgia O’Keeffe, whose mentor was Arthur Wesley Dow.

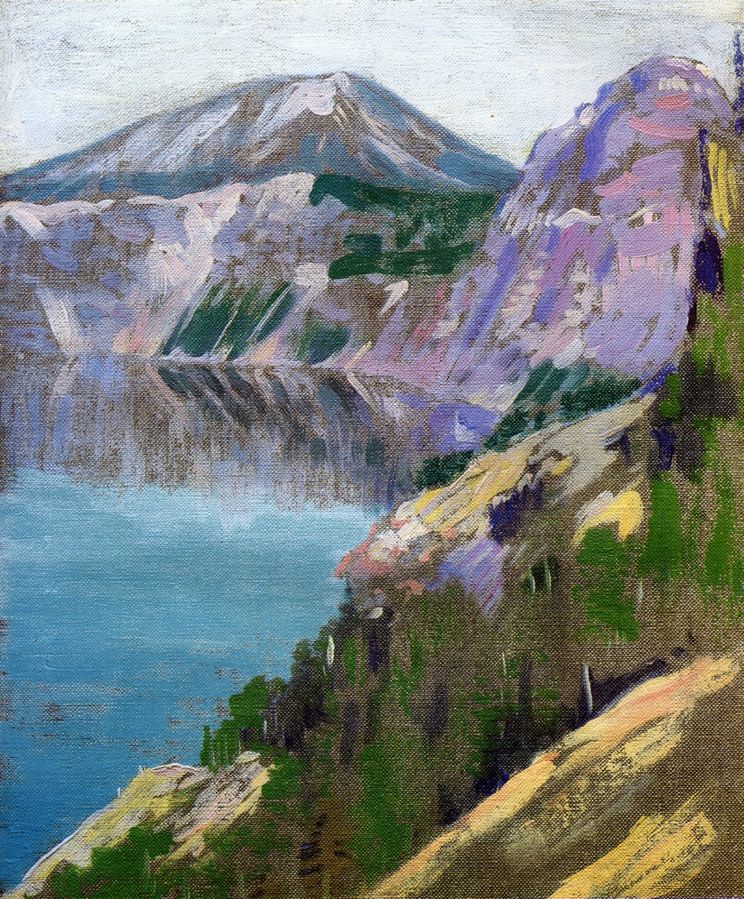

Dow was a painter representing landscapes mixing Impressionism and Japanese aesthetic principles. Yet, he is mostly remembered today as an important art educator, while O’Keeffe — who also taught — is the one celebrated for painting lyrical nature representations.

As Kusama and O’Keeffe’s connection wasn’t a traditional mentorship, they didn’t have this hierarchical relationship. Rather, it was based on mutual respect towards each other.

Despite this formality, O’Keeffe was really involved in her role as protector. Just like Kusama, O’Keeffe was from the countryside, raised on a farm in Wisconsin. She experienced beforehand what it is to be a young woman in New York’s merciless art scene.

Georgia O’Keeffe was one of the few women who managed to break through the glass ceiling during her lifetime. Despite her accomplishments, the artist fought against misogynistic approaches to her art. Her gender identity still prevails today. She is sometimes called the “mother of American Modernism” even though she never actively took part in any groups. Also, her work is seen as feminine because she painted flowers, even though she also depicted skyscrapers and animal skulls. The close-up depiction of flowers is interpreted as a metaphor for female genitalia. Yet, O’Keeffe felt that the “subject matter of a painting should never obscure its form and color, which are its real thematic contents”. This means that forms, composition, and their visual effect were more important than interpretation.

O’Keeffe was married to Alfred Stieglitz, a photographer and gallerist who had great influence in the New York art scene. Even though Stieglitz is the one who exhibited Georgia O’Keeffe for the first time, the painter gained recognition on her own. After her husband’s death in 1946, O’Keeffe worked remotely from the Big City. She still remained a respected figure, proving that a woman doesn’t necessarily need a man to be a great artist.

Similarly, Yayoi Kusama had only one lasting relationship with American artist Joseph Cornell, a self-taught artist as well. Cornell knew important figures in the art world such as Marcel Duchamp, Mark Rothko, and Andy Warhol. Yet at no time did she use the infatuation he had with her to advance her own career. Unfortunately, the artist’s ethics differed from those of her male counterparts and this strongly impacted her.

From the late 1950s to the 1970s, Kusama led her career alongside different artistic moments: Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, Minimalism… All these movements were mainly male-oriented. For a long time, Lee Krasner was only remembered as Pollock’s wife. Michael West, an artist excluded from the Abstract Expressionist movement, is another example showing it wasn’t easy for women to gain recognition.

As for Kusama, she rubbed shoulders with acclaimed artists such as Donald Judd and Andy Warhol. As with the latter, she wanted her art to make her famous. However, instead of having a healthy competitive streak, several male friends robbed her of her ideas.

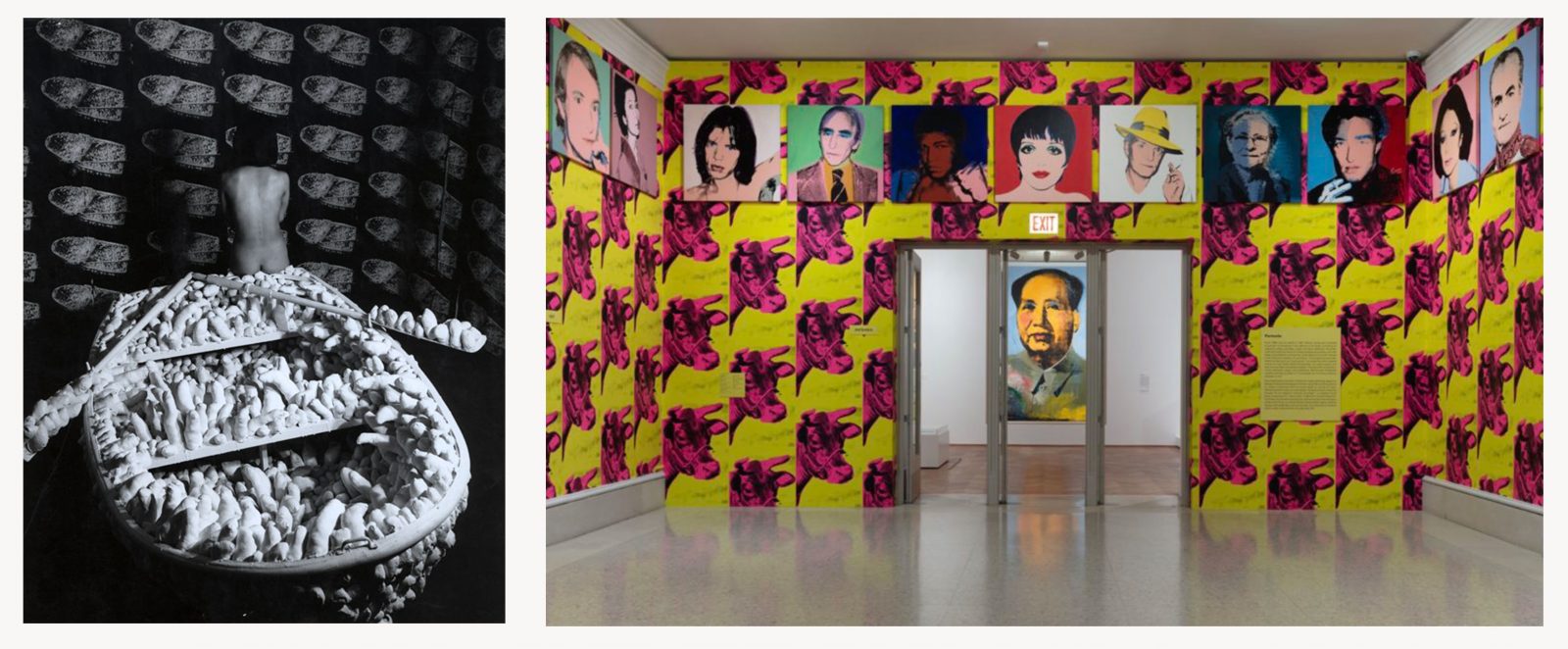

In June 1962, Yayoi Kusama participated in a show with artists such as Claes Oldenburg, James Rosenquist, and Andy Warhol. Kusama was the only woman and the only person of color in the group. Although she wasn’t as renowned as her colleagues, her armchair covered with phallic tentacles of fabric created a big sensation. A few months later Claes Oldenburg’s career launched with his “soft sculptures.” While he previously worked with ceramic and plastered burlap, Oldenburg started to do big sculptures made entirely of fabric.

Similarly, Lucas Samaras’ work suddenly evolved eight months after seeing Kusama’s first Infinity Mirror Room. From small assemblage boxes, the mixed-media artist made a human scale box, entirely mirrored.

Nowadays, Yayoi Kusama is the first artist one thinks of when referring to infinity rooms. At that time though, it was really hard for her to watch the appropriation of her ideas, one by one.

The artist who benefited the most is Andy Warhol. The King of Pop Art had a major retrospective organized in 2019. A reproduction of the Cow Wallpaper covered the whole entrance of the exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago. Warhol presented this display for the first time in 1966 at the Leo Castelli Gallery and has since been credited for the concept. The truth is he literally took it from Yayoi Kusama’s One Thousand Boats show in 1964.

Not only was Yayoi Kusama a woman, but she was also a foreign artist. This certainly made it easier for her male counterparts to remorselessly take credit for her original ideas.

O’Keeffe was familiar with the shadow of men’s privilege in the art world. She felt that the double outsider status of her protegee, although talented, would be hard to deal with in New York. This is certainly why she suggested Kusama join her in Santa Fe. Kusama declined the invitation several times, thinking that only in New York could she gain international recognition.

Still, at the end of the 1960s Kusama’s contributions to contemporary art were overlooked. Moreover, the media paradoxically criticized her for seeking too much attention with sensationalist self-promotion. Deeply affected by this situation, Yayoi Kusama decided to go back to Japan in 1972.

The young Kusama thought she could become famous by living the American dream. Despite all her efforts, she gained little notoriety there. Ironically, she only received international recognition after she entered a psychiatric hospital. As Georgia O’Keeffe before her, she voluntarily withdrew from the hustle and bustle of society to focus on what is most important: interacting with the world through her creativity.

It is as if one makes the best art only when one feels at home, no matter what “home” is.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!