The Art of Science—Versailles at the Science Museum, London

Have you ever wondered how it would feel to witness the grandeur and opulence of the 18th-century French court? Then you might want to go to London.

Edoardo Cesarino 19 December 2024

15 April 2024 min Read

Music of the Mind, on view at the Tate Modern in London until the 1st of September, is a celebratory career retrospective of the work of Yoko Ono. Ono may be widely known for reasons other than her art, however, she is also one of the more notably female artists of the contemporary era. Moreover, she has pioneered new ways of expression in her decidedly multimedia work, from performance to film-making, installation, drawing, and music, since the 1960s.

Perhaps properly situated in the midst of the exhibition, one can listen to an audio recording of a roughly 12-minute-long speech by Yoko Ono given at the Destruction in Art Symposium (DIAS), held in London in 1966. The speech offers valuable insights into Ono’s process of art-making.

The first idea was to let the audience participate.

Speech delivered at the Destruction in Art Symposium (DIAS), London, 1966

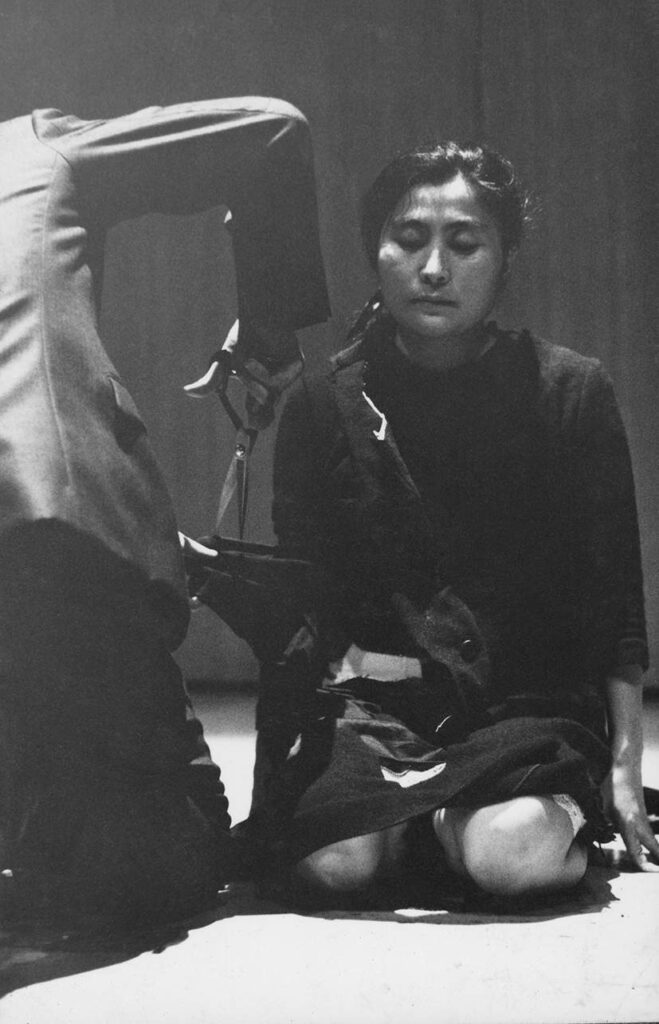

The viewer’s engagement, indeed, activation, as a participant, is a leitmotif of Ono’s work. One amongst various examples of this leitmotif in action in her work is Cut Piece, a performance where Ono, alone on a stage, waits for people in the audience to approach and cut a piece of her clothing. The exhibition collects photography and film documentation of this work’s original performance, while recreating some of the other works, or situations, that Ono conceived of, inviting the audience’s participation. Such works include Painting to be Stepped On, and Shadow Piece, where viewers were invited to draw their own shadows on a canvas that increasingly came to be populated with stylized figures.

Yoko Ono, Cut Piece, 1964, photographed 11 August 1964, printed 2024. Performed by Yoko Ono in Yoko Ono Farewell Concert: Strip Tease Show, Sogetsu Art Center, Tokyo, Japan. Courtesy the artist © Yoko Ono Photograph by Minoru Hirata. Tate Modern.

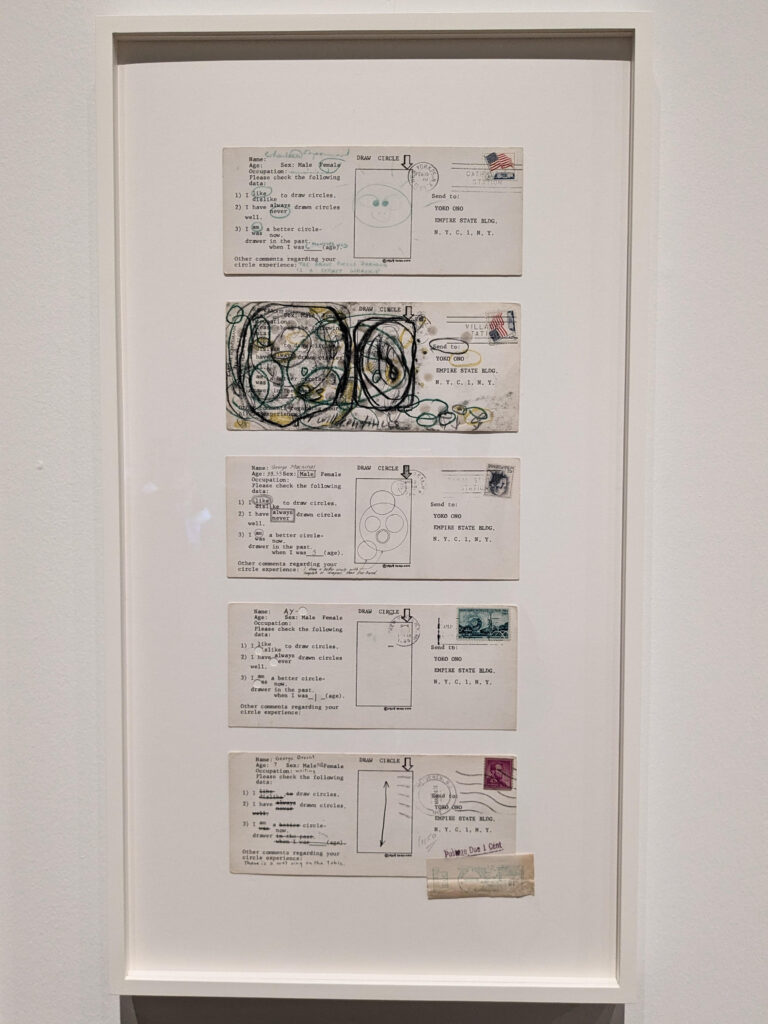

Another artwork on display contains a few postcards from the Draw Circle Event that Ono sent to other artists. The postcards contained questions and instructions that the artists had to address about drawing circles, an apparently useless action, yet charged with artistic self-conscience.

As the title itself stresses, by calling this an ‘event,’ the artwork becomes entrenched with the participatory event that has given shape to it, its outcome becomes contingent upon the particular situation and contributions that happen or have happened. The elements of chance and simplicity in all these works clearly resonate with the aesthetic of the avant-garde movement Fluxus, in which Ono took part since its beginning.

Yoko Ono, Draw Circle Event, 1964-5, Tate Modern, London, UK. Photograph by Barbara Bravi. Selection of 5 postcards responses sent by the following artists: Charlotte Moorman, Carolee Schneemann, George Maciunas, Ay-O, George Brecht.

Interestingly, those of Ono’s works that were purposefully ‘unfinished’ therefore held more potential for inviting audience participation. In the aforementioned DIAS speech, she states: “I consider all my pieces to be rehearsals […] incomplete pieces that should be finished in a dream or something.” Later in 1966, Ono held a solo show at the Indica Gallery in London with the title Unfinished Paintings and Objects, exhibiting mostly white and transparent objects, to which the viewer was invited to add color, or to play with, like for the White Chess Set re-proposed in this exhibition.

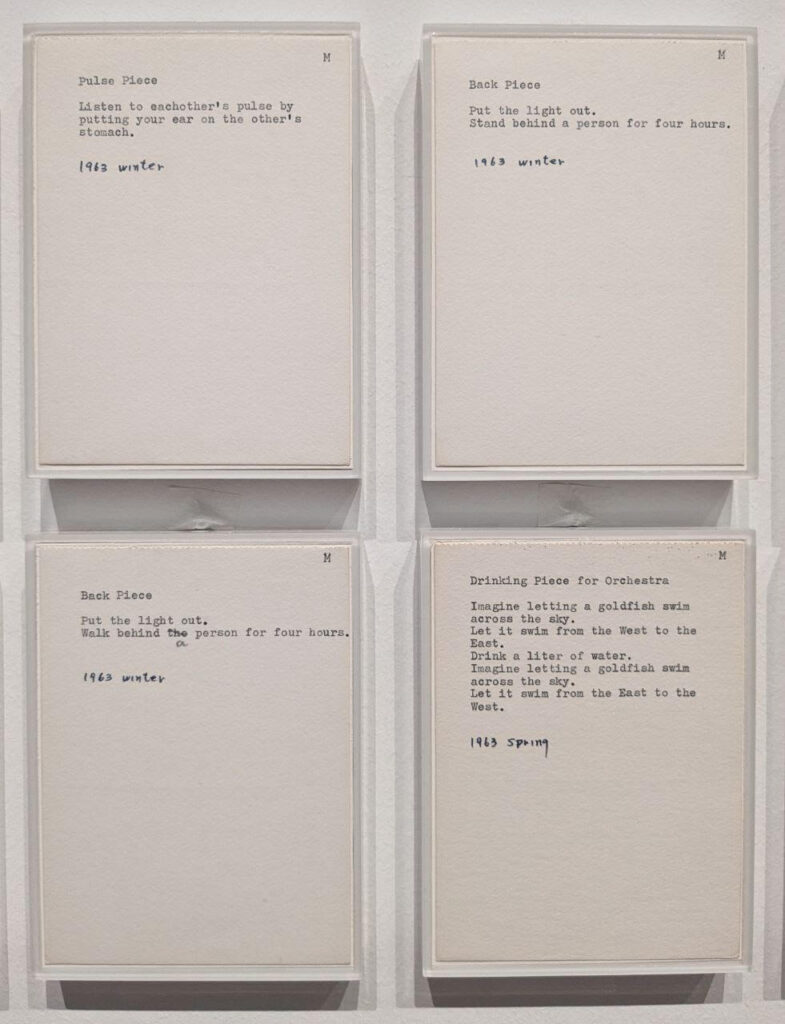

The most representative artworks in this regard are probably the Instruction Paintings, consisting of small pieces of paper listing the instructions to create an artwork: they embed the possibility of an artwork, leaving to the viewer the task to realize it, or just imagine it. Fifteen of them were already included in Ono’s first solo exhibition in 1961 at the AG Gallery in Manhattan.

Yoko Ono, Typescripts for Grapefruit, 1963-1964, Tate Modern, London, UK. Photograph by Barbara Bravi.

Instructions for artwork creation were also collected in the famous Grapefruit book, divided into five sections (music, painting, event, poetry, and object), all on display in the exhibition: from instructions to listen to each other’s pulse, to those for the work Drinking Piece for Orchestra, just to mention a few. They incorporate a compelling meta-artistic reflection that not only invites the contribution of the viewers but also leads them to question what defines an artwork, which rules can encode it, and whether it is really the artist or the audience that constructs it.

Yoko Ono, Half-A-Room, 1967, Tate Modern, London, UK. Photograph by Barbara Bravi.

Another installation, with the title Half-A-Room, shows how Yoko Ono is fascinated, along with the unfinished, by the evocative power of severed objects from everyday life: two chairs, a cupboard, a pair of shoes, a radio, and other objects lie down cut in half and covered in white paint, perhaps manifesting another way of portraying a sense of incompleteness.

Participation, in Yoko Ono’s work, is meant as functional in or to the viewer’s personal experience:

I am more interested in happenings that are more personal, happenings that you experience for yourself […] I try to give something that is an experience that is not so much for the whole, but for each individual.

Speech delivered at the Destruction in Art Symposium (DIAS), London, 1966

Several of Ono’s artworks can indeed be seen as the starting point of an experience: examples are the Apple, promising to the buyer the “excitement of watching the apple decay,” and other sculpture-objects like Pointedness and Forget It, accompanied by engraved instructions meant to anticipate and shape the viewer’s personal experience.

These pieces echo another main theme of Yoko Ono’s production, the appeal to ready-made objects reminiscent of everyday actions. The poetry of simple actions is found already in the Lighting Piece, an early film and performance taking shape around the instruction “Light a match and watch till it goes out.” Everyday sounds are also explicitly introduced in the acoustic background of her shows, from her own coughing of the Cough Piece to the noise of a flushing toilet of the Toilet Piece.

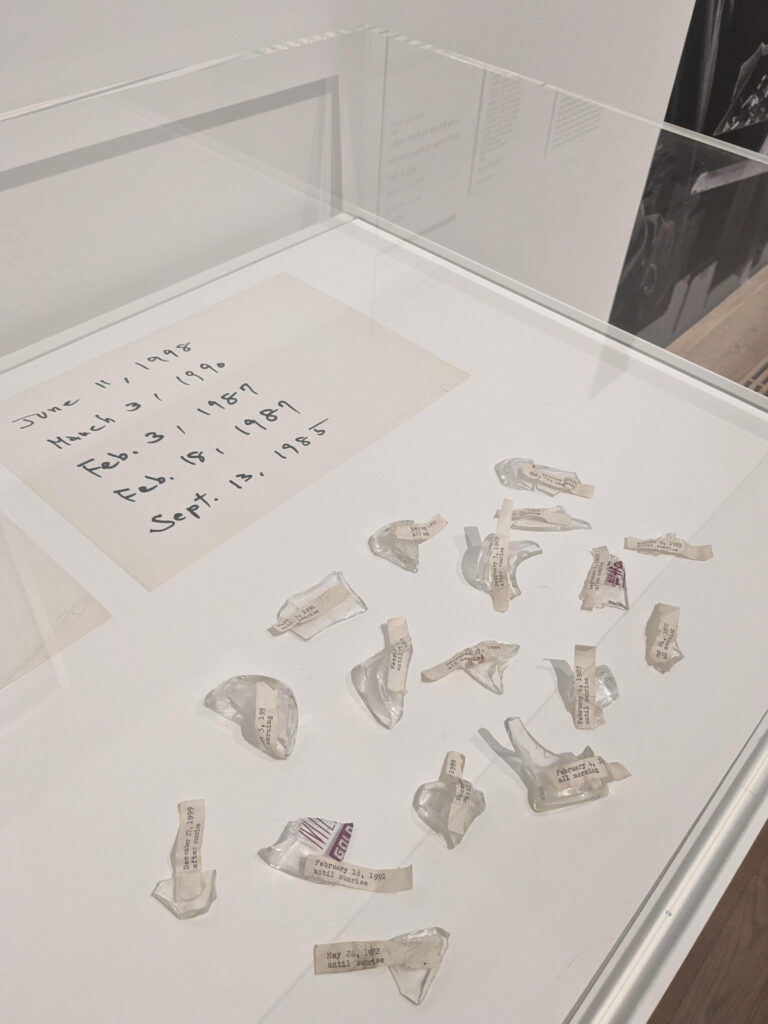

Yoko Ono, Future Mornings from the Morning Piece, 1964, Tate Modern, London, UK. Photograph by Barbara Bravi.

In the film Some Young People, portraying rebellious young artists in Tokyo, Ono states “art is nothing special, anybody can do it.” During the film, she is seen leaving flowers along the streets and performing her Morning Piece. In the event tied to this piece, Ono sold shards of milk glass bottles, each labeled with the date of a future morning. The hand-written notice for the event, displayed in the exhibition, contains the practical details – the type of mornings on sale and the price list – and the instructions given to the participants – “people were asked to wash their ears before they came,” and “each person was asked to pay the price of ‘morning.'” When parts of the day are ironically sold as artworks, such as in this work, it is difficult to think of more literal ways about the coincidence between art and daily life.

Yoko Ono, Peek Piece, 1967, performed at the Bluecoat, Liverpool, UK. Photograph by Sheridon Davies. LiverpoolEcho.

The broken glass fragments of the Morning Piece recognize the possibility of attributing an artistic value to destruction, a theme that Yoko Ono discussed with other artists at the DIAS. Hiding and disappearing can be seen as softer forms of destruction that emerge among the themes of her performances: examples are the Peek Piece, where she glances at the audience while staying hidden behind a white box, or the Wrapping Piece, where she asks the audience to wrap her with gauze until she disappears, completely hidden by it. These performances came to be part of Music of the Mind, a series of events performed in Liverpool and London in 1966/1967, and which gives its name to the title of this Tate Modern exhibition itself.

The only kind of intentional destruction that I am interested in […] is a kind of destruction that brings about larger construction.

Speech delivered at the Destruction in Art Symposium (DIAS), London, 1966

Exhibition view, foreground: Yoko Ono, A HOLE, 2009; background: Yoko Ono, Helmets (Pieces of Sky), 2001, Tate Modern, London, UK. Photograph by Barbara Bravi.

This reflection seems to permeate Ono’s art until much later, when in 2009 she creates the artwork titled A HOLE, consisting of a glass pane with a hole in the center due to a bullet shot. The instruction engraved at the bottom, “Go to the other side of the glass and see through the hole,” alludes to the creative power of a destructive action, while exposing a surreal element that characterizes many of Ono’s works: The broken glass around the hole in reality makes us struggle to see clearly the other side through the hole, and why should one do that given that the glass is transparent?

Yoko Ono, Helmets (Pieces of Sky), 2001, from Between The Sky and My Head exhibition, 2008 at Baltic Centre For Contemporary Art, Gateshead, UK. © Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art.

The installation immediately next to it, Helmets (Pieces of Sky), is composed of a series of military helmets arranged upside down, in such a way as to collect pieces of sky that the viewer can take away. This simple inversion of the helmets’ position performs a powerful symbolic conversion, whereby images of war are mapped into images of positive transformation, to which each of us is invited to contribute piece by piece.

Ono’s activism for peace is also accompanied by a feminist commitment, as iconically conveyed by Freedom, a short film portraying Ono while she struggles to take off her bra: her body becomes protagonist, in an act of self-representation as well as self liberation.

Yoko Ono and John Lennon, Bed-in for Peace, Amsterdam, 1969. Courtesy Yoko Ono. Photograph by Ruud Hoff. Image: Getty Images / Central Press / Stringer.

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind provides a comprehensive overview of Yoko Ono’s production that cuts across decades. It contains abundant footage and photographic material on the ground-breaking creative events that she organized and participated in, like music performances with John Cage and David Tudors, it gives us the chance to re-enact happenings like the Bag Piece, and it offers the opportunity to get acquainted with Ono’s experimental music production. Furthermore, it more extensively recalls her activism for world peace, including a long video recording of the Amsterdam and Montreal Bed-ins for Peace performed with John Lennon, with whom she established, as is well known, a personal and artistic partnership.

For her elaboration upon the significance of the event for participatory art, for her clever investigation into the creative role of an artwork’s instructions and destruction, and for much more, Yoko Ono stands out as one of the most important pioneers of conceptual art. And this exhibition pays rich tribute to all of these contributions.

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind runs until September 1, 2024 at Tate Modern in London, UK.

Author’s bio:

Barbara Bravi is an art lover originally from Italy but currently based in London. She makes a living by working as a university lecturer in biomathematics, yet she spends most of her free time visiting art exhibitions. As such, she is deeply fascinated by the intersections between art, mathematics, and science in general.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!