The Ghosts of Yūrei-zu

Religion was a big inspiration for this art genre. According to Shintō and some sects of Buddhism, when a person dies, their reikon (soul) leaves their body and enters purgatory, until the person’s proper funeral. After the funeral, the reikon rejoins the person’s ancestors in the afterlife and returns to the living world only every August during the Obon festival.

However, a reikon can become a yūrei, if the person dies violently, unexpectedly, or is overwhelmed by negative emotions like vengeance. The yūrei lingers in the realm of the living until it completes its unfinished business. Intriguingly, a yūrei’s intentions may not be malicious, yet the results of their actions are damaging or hazardous to humans.

Historical Background

Supernatural beings and gory, grotesque, and unsettling scenes were depicted in Japanese painted scrolls dating back to medieval times. This tradition lasted for centuries, laying the groundwork for yūrei-zu, as well as the more gruesome chimidoro-e (bloody pictures) and muzan-e (cruel pictures). These artistic themes became very popular during the Edo period. Yūrei-zu particularly thrived in the mid to late 19th century, coinciding with the rise of ghost-themed kabuki plays and tales (kaidan). Scholars attribute the enduring fascination with the occult of this time to the tumultuous social conditions of the late Edo period, marked by the oppressive Tokugawa regime, the onset of Westernization, and various natural disasters.

The Tempō Reforms: An Attempt to Censor Art

The Tokugawa regime’s goal was to return Japan to its feudal and agrarian origins. Thus, in 1842, it enacted the Tempō Reforms, a comprehensive set of laws impacting various aspects of life including the economy, military, agriculture, religion, and art. These reforms forbade artists and publishers from creating or distributing images of geisha, oiran courtesans, and kabuki actors, as they were considered harmful to public morals.

So, artists turned to yūrei-zu to critique social and political issues by replacing real figures, particularly the ruling elite, with supernatural beings. Gradually the government prohibited yūrei-zu and ghost plays. However, the Tempō Reforms were unsuccessful, lasting only until 1845. Ultimately, yūrei-zu served as a form of catharsis for the people of the Edo period, allowing them to confront their fears.

Characteristics of Yūrei-zu

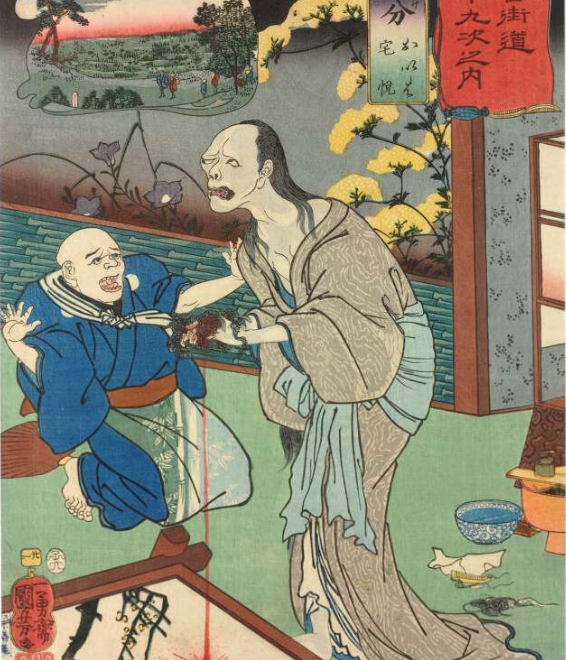

Yūrei-zu represents a wide variety of spirits. It includes various forms of ghosts, ranging from animals and mythical creatures like cats, foxes, and dragons to male warriors and predominantly disappointed females. They usually have long, messy black hair and wear white or pale-colored kimonos, suggestive of funerary attire such as katabira or kyōkatabira. Their garments feature long, flowing sleeves, sometimes accompanied by a triangular forehead cloth, a nod to Japanese funeral customs.

Possessing a thin and fragile frame, yūrei-zu often extend their arms with hands loosely hanging from the wrists, and are bodiless below the waist. They are also frequently depicted with hitodama, meaning floating flames in shades of green, blue, or purple. Moreover, the spirits exhibit transparency or semi-transparency and typically emerge at night while avoiding running water. Notably, their true ghostly form is revealed when reflected in mirrors or water surfaces, adding an eerie dimension to their nocturnal presence.

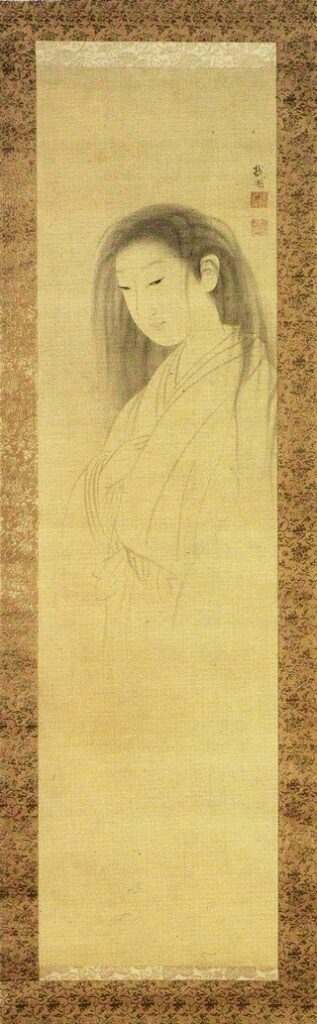

The Ghost of Oyuki by Maruyama Ōkyo

The earliest yūrei-zu is probably The Ghost of Oyuki by Maruyama Ōkyo. He was one of the most important artists of the 18th century and the founder of the Maruyama School of Art.

The artwork, as seen below, is a silk scroll painting, dating back to the second half of the 18th century. It depicts a female ghost in very soft colors that slowly fades into transparency. The woman is probably a geisha, Maruyama’s lover, who died at a young age. Maruyama saw her in his sleep and painted her portrait.

Artists of Yūrei-zu

There were many artists of the genre, including Utagawa Kunisada, Katsushika Hokusai, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, and Yoshitoshi Tsukioka.

Utagawa Kunisada, also known as Toyokuni III, was a prominent ukiyo-e artist of the Edo period. He produced many artworks, including several prints with kabuki actors, beautiful women, and scenes from Japanese mythology. While not primarily known for his yūrei-zu, Kunisada did create prints with supernatural themes, often intertwined with kabuki theater and folklore.

Katsushika Hokusai is perhaps most famous for his iconic print series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, which includes the famous work The Great Wave off Kanagawa. However, he also painted yūrei-zu in his later years. Notable among his ghostly works is the series One Hundred Ghost Stories (Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai), where he depicted various eerie and spiritual beings.

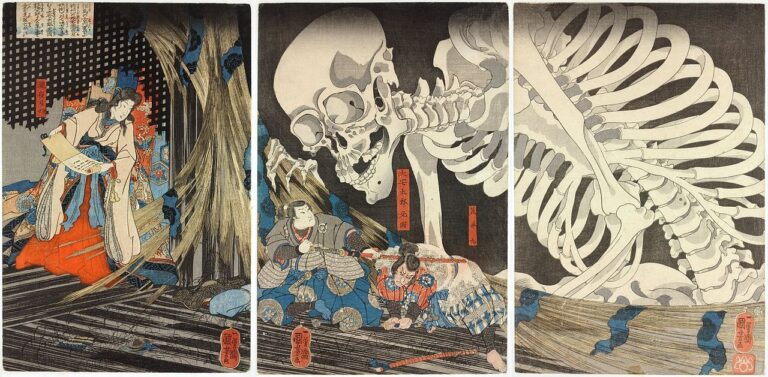

Another ukiyo-e master who delved into the yūrei-zu genre was Utagawa Kuniyoshi, an artist celebrated for his dynamic and imaginative prints. He was fascinated with the supernatural and created numerous prints featuring ghosts and demons. Kuniyoshi’s contributions to yūrei-zu often showcased his bold and inventive style, depicting haunting and macabre scenes.

Last but not least is Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, known for his powerful and emotionally charged prints. His artworks covered a wide range of subjects including historical events, landscapes, and ghost stories. He was particularly interested in the darker aspects of Japanese folklore. He created several yūrei-zu series, such as New Forms of 36 Ghosts and One Hundred Aspects of the Moon.

Overall, these artists played significant roles in shaping the representation of yūrei-zu in Japanese art, each contributing their unique styles and interpretations to this enduring tradition.