Lotus Temple and the Bahá’í Faith

The Lotus Temple is renowned for its distinctive lotus shape. A prominent Bahá’í House of Worship in New Delhi, the temple embodies...

Maya M. Tola 27 January 2025

Zaha Hadid was undoubtedly one of the most important architects of the last hundred years. She forged her individual style and blazed a trail for women in architecture, being the first woman to be awarded the Pritzker Prize in 2004. Yet her work also caused many controversies, often described as insensitive to its surroundings, or because of the excessive cost of construction and maintenance (which generally is one of the most popular complaints about architecture). Her choice of clients was also often disputed. Take a look at a selection of 10 designs by Zaha Hadid and judge for yourself.

Zaha Hadid was born in 1950 in Iraq, she studied mathematics before embarking on her adventure with architecture. She graduated from the Architectural Association School of Architecture in 1972. There she was one of the students of Rem Koolhaas, and once done she planned to conquer the world. Hadid incorporated painting and abstraction into her workflow to explore ideas more freely. While many of her designs were widely published and admired, they were rarely built.

That is until in 1993 Rolf Fehlbaum, then the director of the furniture company Vitra invited Hadid to design a small fire station for the factory. And Hadid took the commission, that others may think minor, with all seriousness. Her design is daring with bold lines and audacious interplays of heavy and light forms. It is far from the organic forms she used in her later designs. It also clearly shows her playfulness and expertise when it comes to toying with geometry and our sense of perception. This building launched a new phase in her career.

Zaha Hadid, Vitra Fire Station, 1993, Weil am Rhein, Germany. Archello.

When in 2004 Hadid became the first woman to receive the coveted Pritzker Architecture Prize, the construction of the BMW Central Building in Leipzig was well underway. The project’s scale was massive, and the concept was daring. Hadid used the opportunity to connect three existing factory buildings with her central design. When you look at the plan she did it as if she was simply connecting the dots, and yet the effect is stunning and energizing. It becomes the nervous system of the whole industrial space and is also its visual core.

As much as the building is administrative in its function, housing meeting rooms and public relations spaces, Hadid made sure it remained intricately connected with the industrial process. She achieved it by weaving into it the conveyors transporting cars from one construction shed to the other. This way the cars that are being produced here are front and center of everyone’s mind, bringing a unifying sense of purpose to everything that is being worked on.

Zaha Hadid, BMW Central Building, 2005, Leipzig, Germany. Photo by Thomas Mayer/ERCO.

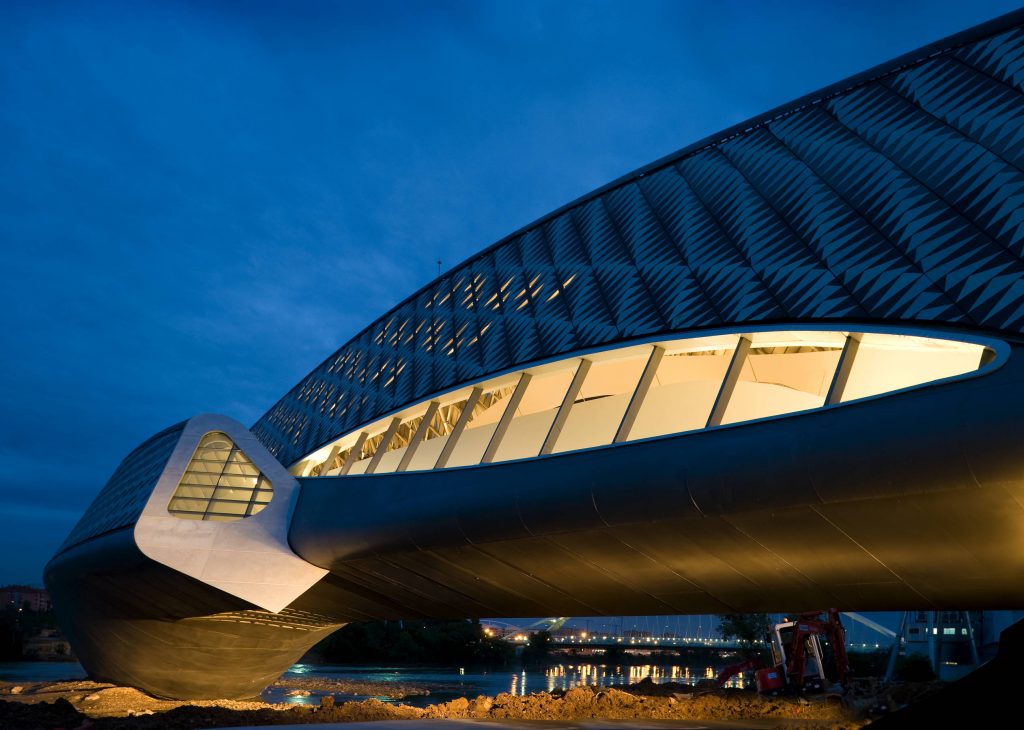

By 2008 Hadid, at her third RIBA European Award, received a Thomas Jefferson Medal in Architecture. Her career was then in full swing and her designs were more daring than ever. The city of Zaragoza held the Expo exhibition in 2008 and the Bridge Pavilion became the gateway to the event. Not only did it provide visitors a passage through the river Ebro, but also houses a multi-level exhibition area. Hadid did not want her bridge to be invisible, just the opposite. She made it a statement, cutting a bold line across the river. The project has the organic feel that came to be associated with Hadid’s work, but it also retains the sense of weight, it is not a flimsy floating structure, but rather a bridge that can also be seen as a shelter.

Zaha Hadid, Bridge Pavilion, 2008, Zaragoza, Spain. Zaha Hadid Architects.

MAXXI gave Hadid the Stirling Prize, by then she was honored with prizes annually. The original design comprised of five structures, but only one was completed. The building is a geometric composition that eradicates the borders between inside and outside spaces, both become intertwined in a project that goes out of its way to make an impression. A museum becomes a work of art in its own right. Its bold forms are a lot more intimidating than for example the famous Bilbao Guggenheim, but they also draw you in, inviting you to join the adventure of modern art. It can be daunting but it can also be fun if you let it.

Zaha Hadid, MAXXI National Museum of 21st Century Arts, 2010, Rome, Italy. Musement.

The Guangzhou Opera House was an important project to Hadid, as it opened a new market for her, becoming her first commission in China. Also in the competition, her design was selected over one by her mentor Rem Koolhaas. It may have also felt a bit more personal, as one of the sore points of Hadid’s career was a never-constructed Cardiff Bay Opera House, that Hadid designed in the mid-1990s, the Guangzhou project may have felt a bit like closure and vindication.

The Guangzhou Opera House is on the banks of the Pearl River and fittingly has been shaped as two stones with surfaces smoothed by the flowing water. Its stunning organic forms are carried through in its interiors, including the fantastic auditorium with illumination bringing to mind a starry sky.

Zaha Hadid, Guangzhou Opera House, 2010, Guangzhou, China. Secret-World.

Continuing the water-related vein we cannot skip the much-disputed London Aquatics Centre. Designed and built for the 2012 Olympics, the design was reworked several times to get the cost under control, but it still went wildly over the original estimates. Also for the Olympics, the building had additional parts that have since been removed and were possibly recycled. What we are left with is a beautiful and calming form of the sweeping gentle wave of the roof.

Zaha Hadid, London Aquatics Centre, 2011, London, UK. Photo by Rick Ligthelm via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0).

One of the most striking designs by Hadid. It is a building that not only showcases her imagination but also the skill it takes to convert a dream into a building. The center was supposed to become the cultural heart of the redeveloping Baku. The city is saddled with a lot of post-Soviet history and with heavy architecture from that time. This building looks firmly to the future, its undulating lines gently folding the surrounding landscape in. It is one of the examples of Hadid’s sometimes questionable choice of clients. On one hand, everyone does that, on the other, there is a question of moral responsibility. Can architecture really transform society, or does it become a hugely expensive trophy legitimizing powers that be, whether they serve the good or bad?

Zaha Hadid, Heydar Aliyev Center, Baku, Azerbaijan. Inside Arabia.

Yet another example of Hadid’s controversial projects. Not because of the design itself, but again due to the client. The Football World Cup in Qatar is controversial in its own right as an event, so by association Hadid’s acceptance of the project had to be too. The stadium has been completed since her death, but her decision to accept the commission was questioned when she was still alive.

If we leave for a second the moral side of things to indulgently focus on the aesthetics, we see here how firmly the organic flowing forms had become entrenched in Hadid’s designs by this point. We are very far from the clear-cut lines of Vitra Fire Station. While it shows Hadid’s evolution as an architect it also makes one wonder where she would have gone from here. Would her designs have become even more fluid, or would she have pivoted again? Would the grandiose commissions with nearly unlimited budget endlessly feed her creativity or would they hamper it, because there would be no challenge anymore?

Zaha Hadid, Al Janoub Stadium, Qatar. Metalocus.

Zaha Hadid is mostly known for her architectural designs, but her work was not limited to only that area. She often ventured into smaller forms. They allowed her to explore the detail in a way that full-scale building rarely makes possible. Here we can admire her elegant and ingenious design of door and window handles. She worked on the project with Woody Yao, and originally they designed it for the Puerta America hotel in Madrid. Later Valli&Valli included them in their Fusital collection, so if you’d like to add some Zaha Hadid spirit to your house you certainly can.

Zaha Hadid for Valli&Valli, ZH Duemillacinque door handle, 2008. Metalic Equipment.

As much as you may be able to buy the Duemilacinque handles, getting your hands on the Z-Chair would be a lot more difficult. Hadid’s design has been produced in a limited series of only 24. While visually striking the chair doesn’t seem excessively comfortable. Form over function screams from every edge of this furniture. That said it also embodies Hadid’s style evolution, combining the risky diagonals and organic curves into a form that carries weight, but also challenges us to consider it in its own right.

Zaha Hadid for Sawaya & Moroni, Z-Chair, 2011. cause and yvette.

Zaha Hadid died of a heart attack in 2016. Her legacy continues in the buildings she designed, but also in the work of her studio: Zaha Hadid Architects. I think the fascinating question over the coming years will be the evolution of her style without her. Which direction will the studio take her work? At which point it will cease being Zaha Hadid’s work or style and when would it warrant changing the name? How much is left of a creator in their pupils and collaborators? We’ll find out soon enough as the studio continues working on new commissions.

Hadid’s work and research will also be showcased in the permanent gallery and study center in London that has just been announced by the Zaha Hadid Foundation (ZHF). The Foundation will most probably operate in two locations, currently, there are mentions of the former Design Museum at Shad Thames and the old office of Zaha Hadid Architects in Clerkenwell. ZHF’s founding purpose is to preserve and make publicly available the full range of Hadid’s extraordinary output, and more broadly to advance research, learning, and the enjoyment of related areas of modern architecture, art, and design. It will also actively support young people and students from diverse and complex backgrounds in their quest to become architects, designers, and scholars.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!