Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

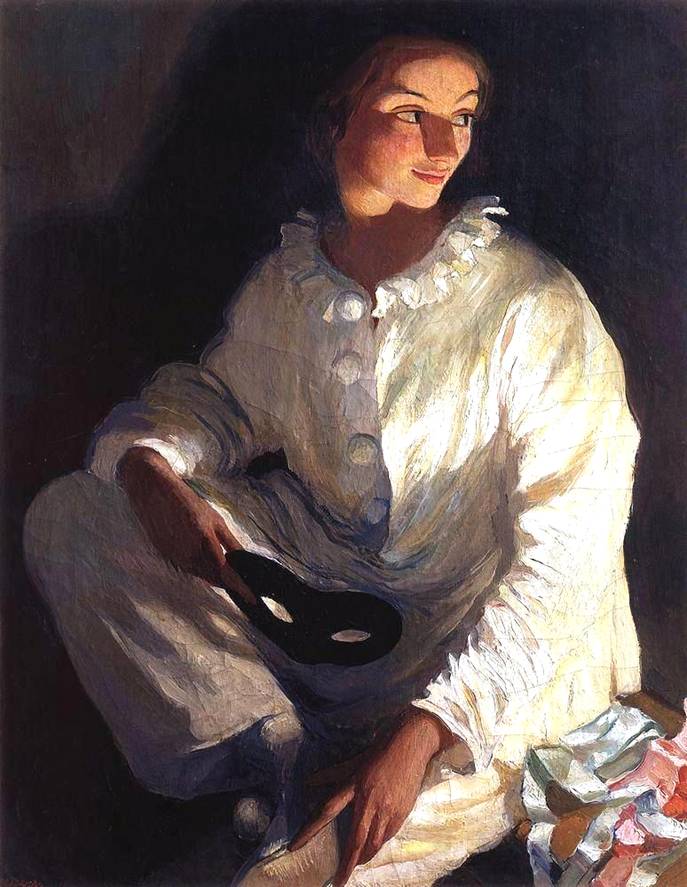

Zinaida Serebriakova (1884–1967) is mostly known for her painting At the Dressing-Table (Self-Portrait). The artist, looking from the mirror’s reflection, smiles at us in many Souvenir shops. But Serebriakova was not just the author of one picture, and definitely not the author of just portrait paintings. She was one of the first women artists to be nominated for the title of academician in Russia.

Let us welcome you to the world of her charming paintings!

Zinaida Serebriakova came from the famous artistic dynasty of Benois-Lanceray, more than 50 representatives of which linked their lives with creative activity in one form or another. Serebriakova’s grandfather, the founder of the dynasty, was a famous architect of the 1850s; Zinaida’s father, Eugene Lanceray, found himself in sculpture. It is not surprising that she had been drawing since childhood.

Serebriakova’s portraits of relatives, family and friends are always light and poetic. They reflect the state of the artist, feeling the fullness of family happiness. At the same time, Serebriakova loved to draw self-portraits. She always appears with radiating femininity, full of romantic excitement. And even when Serebriakova painted other women we can still see her own reflection in their features.

While living in the village of Neskuchnoye, Serebriakova began to draw sketches of peasants. She used to come to the field at dawn to catch the peasants doing their routine. The everyday life of the peasants appears here in the form of a ritual action, full of dignity and grandeur.

In the painting The Canvas Bleaching, the images of peasant women received a classical statism and smooth movement. These women, according to Serebriakova’s thoughts, contain the soul of eternal Russia. Due to the low horizon and the majesty of the figures they look more like ancient goddesses than workers in the field.

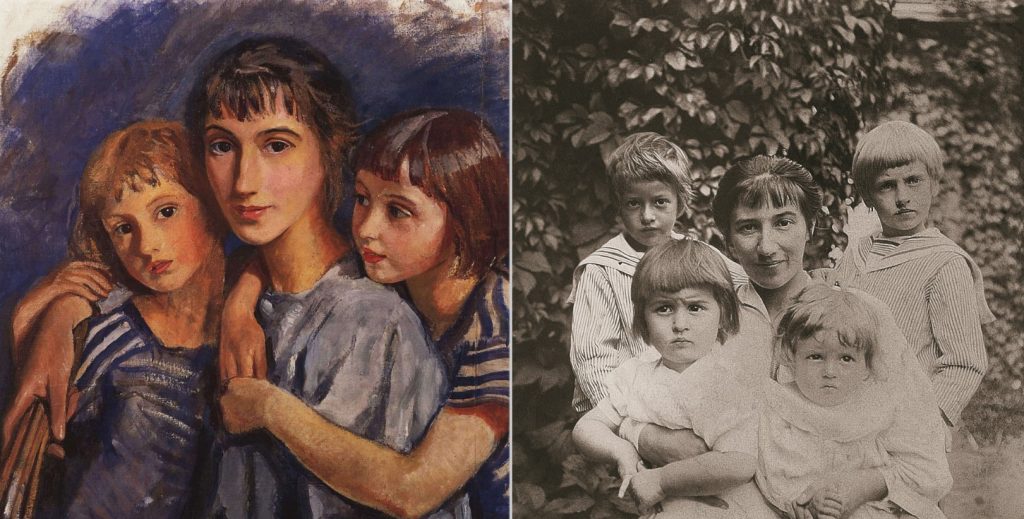

Serebriakova often painted her children, and in this difficult genre she managed to avoid puppet and sentimental images. Children on Zinaida Serebriakova’s paintings do not pose in front of admiring adults – they live their important life as little people who have so many different serious and grown-up things to do. In the painting At Breakfast the peaceful home scene contrasts with the disaster looming on Russia – at this time World War I was already underway.

All Serebriakova’s paintings show her close connection and love for whom or what she portrays, whether it be portraits of friends and family, or the world of ballet dancing, where she found herself after her daughter, Tatyana, entered the choreographic school. Serebriakova also made sketches of the ballerinas from nature: on the days of ballet performances she was allowed to go backstage at the Mariinsky Theater. These paintings help to truly immerse oneself in the atmosphere of theatrical dressing rooms, to catch the feeling of a holiday.

But after many warm and delightful years, with the collapse of the Russian Empire, the life of Zinaida Serebriakova also broke down. Suddenly, she lost her beloved husband, who died in her arms from typhus. They lost money, status and family estates. Serebriakova’s creativity remained her last air, an irresistible desire to see heaven and nature.

In 1924, Serebriakova finally realized that in the new Soviet Russia she had neither prospects nor hope to provide for her family. The only way to exist somehow was to paint ordered portraits, but this rarely happened. The artist decided that there was only one way out – to go to France and work there. The artist left her 74-year-old mother and all four children in Russia.

Until 1940, Serebriakova remained a citizen of the USSR and hoped to be reunited with her family, but during the occupation of France by the Nazis she was threatened with a concentration camp for her connection with the USSR. As a result, to obtain an international refugee identity document, a Nansen passport, she had to renounce her Soviet citizenship.

In 1957, Serebriakova finally got a proposal from the Soviet government to return home. But illness and old age got in the way – she was already over 70, and she practically did not paint. Therefore, the artist did not dare to move.

In 1965, thanks to the effort of Zinaida’s daughter, Tatyana, three of the artist’s exhibitions finally opened at once -– in Moscow, Kiev and Leningrad; preparation for them took five years. Zinaida Serebriakova was already over 80, and she was waiting for news of the public’s reaction to the paintings. The success was deafening. Finally, Serebriakova’s paintings were seen by those who had only heard of her, and the emigrant artist was finally relieved: her art had at last returned home.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!